from the April 2011 issue

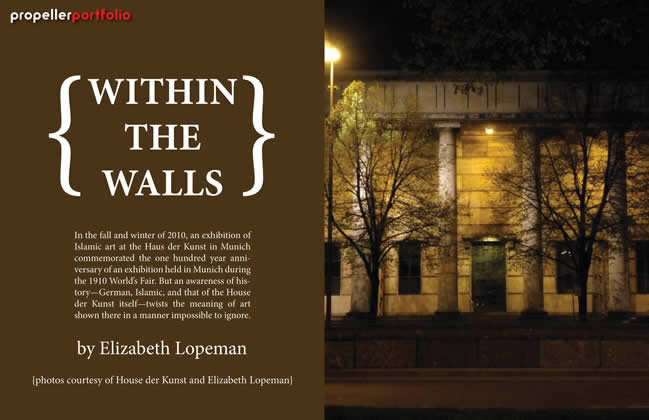

IN 2007, Chris Dercon, director of Munich’s Haus der Kunst museum, (as of April 1 he is at the Tate Modern in London) invited Rem Koolhaas—the Dutch architect responsible for the impressive CCTV headquarters building in Beijing—and Jacques Herzog—who collaborated with Ai Weiwei on the “Birdsnest” stadium in Beijing—to consult on a planned update for the Haus der Kunst. The museum, commissioned in 1933 and completed in 1937, was the first construction project of the Third Reich, and exhibitions there were reserved for the Classical or classically-inspired art of the Greeks and Romans, which Hitler considered to be free of “Jewish influences.” Resting in the regal posture of a lion on the southern end of Munich’s sprawling 1.4 square mile English Garden, the building was designed for Nazi propaganda and the perpetuation of Hitler’s political and artistic ideologies. Art produced by the avant-garde was deemed illegal during the reign of the Third Reich, but a didactic exhibition was held at the Haus der Kunst in July of 1937 to show “degenerate art” or “un-German” art produced by “elitist” and “intellectual” artists such as Kandinsky, Matisse, Chagall, Van Gogh, Oscar Schlemmer, certainly Otto Dix, almost every artist associated with the Bauhaus, and many others. Thousands of people attended the exhibition meant to incite hatred for any art outside of the traditional or favored classical forms. The exhibition was displayed to show the pieces to their disadvantage, as objects of mockery, and many of the pieces were later burned or taken into the private collections of Nazi officers.

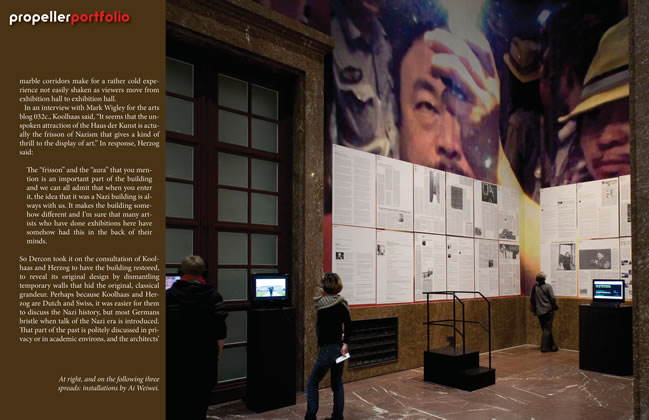

Contemporary use the Haus der Kunst for avant-garde shows, and the preservation of the night club where first Nazi, then American, soldiers congregated to party seems like the best way to transmogrify the meaning of a sinister narrative through a justified disregard or irreverence for the building’s original purposes. In recent years, the museum has hosted exhibitions from International art stars including Anish Kapoor, Paul McCarthy, Marlene Dumas, and Patti Smith. Ai Weiwei, the Chinese political activist who was taken into custody by Chinese authorities in Beijing on April 3 in a crackdown on intellectuals, and whom is yet to be released, did an exceptional job of transforming the halls of the Haus der Kunst to suit his purposes, with pieces that used every square inch of space, if not physically, then playfully and psychically. But the building’s history is rooted in Hitler’s tastes for classical art, and while the reign of the Third Reich is preferred, in Germany, to be sooner forgotten, it’s difficult to separate the ominous architecture of the building from its inception when you enter. Enormous, boxy marble corridors make for a rather cold experience not easily shaken as viewers move from exhibition hall to exhibition hall.

Contemporary use the Haus der Kunst for avant-garde shows, and the preservation of the night club where first Nazi, then American, soldiers congregated to party seems like the best way to transmogrify the meaning of a sinister narrative through a justified disregard or irreverence for the building’s original purposes. In recent years, the museum has hosted exhibitions from International art stars including Anish Kapoor, Paul McCarthy, Marlene Dumas, and Patti Smith. Ai Weiwei, the Chinese political activist who was taken into custody by Chinese authorities in Beijing on April 3 in a crackdown on intellectuals, and whom is yet to be released, did an exceptional job of transforming the halls of the Haus der Kunst to suit his purposes, with pieces that used every square inch of space, if not physically, then playfully and psychically. But the building’s history is rooted in Hitler’s tastes for classical art, and while the reign of the Third Reich is preferred, in Germany, to be sooner forgotten, it’s difficult to separate the ominous architecture of the building from its inception when you enter. Enormous, boxy marble corridors make for a rather cold experience not easily shaken as viewers move from exhibition hall to exhibition hall.

In an interview with Mark Wigley for the arts blog 032c., Koolhaas said, “It seems that the unspoken attraction of the Haus der Kunst is actually the frisson of Nazism that gives a kind of thrill to the display of art.” In response, Herzog said:

The “frisson” and the “aura” that you mention is an important part of the building and we can all admit that when you enter it, the idea that it was a Nazi building is always with us. It makes the building somehow different and I’m sure that many artists who have done exhibitions here have somehow had this in the back of their minds.

So Dercon took it on the consultation of Koolhaas and Herzog to have the building restored, to reveal its original design by dismantling temporary walls that hid the original, classical grandeur. Perhaps because Koolhaas and Herzog are Dutch and Swiss, it was easier for them to discuss the Nazi history, but most Germans bristle when talk of the Nazi era is introduced. That part of the past is politely discussed in privacy or in academic environs, and the architects’ celebratory mood around the history of the Haus der Kunst is a bit surprising, but not entirely refreshing.

Below: installations by Ai WeiWei at the House der Kunst

IN THE FALL and early winter of 2010, an exhibition of Islamic art (or “Muhammadan art”) at the Haus der Kunst commemorated the 100 year anniversary of an exhibition of Islamic art held in Munich during the World’s Fair, called “Meisterwerke Muhammedanischer Kunst,” which translates as “Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art.” Thirty-six of the original 3,600-plus objects were exhibited in 2010, in addition to a large collection of contemporary artifacts from Muslim cultural regions, including films, books, installations, drawings, and paintings. Many of the original pieces from the 1910 exhibition have gained substantial monetary value, and have been absorbed into private collections or are included in museum collections throughout the world, which made them unattainable now. The pieces exhibited at Haus der Kunst in 2010, however, were chosen because following the exhibit in 1910, they became icons of Islamic art that were widely recognized. They are also broadly cohesive in their style, reflecting a vast cultural region that lacked a propinquity to Europe in 1910, with the exception of luxury goods supplied to kings and queens, primarily with an aesthetic of calligraphic, scrolling inscriptions, or similarly interlaced depictions of foliage and tendrils etched or hammered into brass urns and weapons, enameled onto glass lamps, or woven into rugs. The exhibition catalog concedes that “The all-embracing global term ‘Islamic art’ falls into fragments in the face of contemporary art.” In spite of this difficulty, the recent exhibition’s thrust was to look at the ever shifting exchanges of styles and influences between East and West, and how they have influenced viewers’ perceptions today.

The 1910 and 2010 exhibitions both made a point of showing artifacts in the context of the exhibition rather than in the context of their cultural origin—in other words, in a manner that “stages the Orient.” Muslim regions were considered exotic, sometimes erotic, and very much the origins of the “stranger,” “alien,” or “other,” and the agenda of the 1910 exhibition in particular was to show the artifacts as masterpieces in their own right. In an essay in the 2010 exhibition catalog, Avinoam Shalem (the curator) and Eva-Maria Troelenberg make reference to the 1910 exhibition, saying, “The exhibits were dispersed generously in the amply arranged exhibition halls, either free standing or set against the neutral background of unadorned showcases or large wall areas.” While a similar approach to displaying artifacts was taken in 2010, with attention to their connectivity, the Shalem/Troelenberg essay explains:

The 1910 and 2010 exhibitions both made a point of showing artifacts in the context of the exhibition rather than in the context of their cultural origin—in other words, in a manner that “stages the Orient.” Muslim regions were considered exotic, sometimes erotic, and very much the origins of the “stranger,” “alien,” or “other,” and the agenda of the 1910 exhibition in particular was to show the artifacts as masterpieces in their own right. In an essay in the 2010 exhibition catalog, Avinoam Shalem (the curator) and Eva-Maria Troelenberg make reference to the 1910 exhibition, saying, “The exhibits were dispersed generously in the amply arranged exhibition halls, either free standing or set against the neutral background of unadorned showcases or large wall areas.” While a similar approach to displaying artifacts was taken in 2010, with attention to their connectivity, the Shalem/Troelenberg essay explains:

The recent exhibition, ‘The Future of Tradition – The Tradition of Future,’ in the Haus der Kunst, also sets new parameters for staging the art of the ‘Other.’ It aims at suggesting that a new tendency of what Said calls “extrapolation” appears in the periphery, in the sphere defined as ‘out of the centre’ but which demands its full recognition (Said1994, p. 293).

And in another catalog essay, Kaelen Wilson-Goldie discusses how Susan Sontag, in her essay “Against Interpretation,” asks viewers to experience artworks as complete works without a relationship to their context. Shalem and Troelenber go on to say:

It must be emphasized, however, that it is not a neutral or universal view this exhibition seeks to establish—it is a laboratory for 21st-century questions, hopefully breaking ground for the future exhibition concepts and museum displays that will show and think of Islamic art alongside the art of the West—without denying ‘Otherness,’ but with a new agenda of generating mutual visual understanding; beyond sectarian or nationalistic tendencies and beyond worn out paradigms such as ‘parallels’ or ‘influences’ which automatically imply hierarchies or one-way trajectories.

The 1910 and the 2010 exhibitions were both conceived as representations of art in the context of Muslim regions, and so while we can enjoy the pieces individually as masterful artistic expressions, in this milieu it is impossible to extract them from context. Shalem and Troelenberg state that the exhibition doesn’t seek a “neutral” approach to viewing the show, and how could it? How can viewers be asked to look “beyond sectarian or nationalistic tendencies” while viewing pieces that are titular reflections of their provenance? Sontag makes an excellent point that each piece of art should be evaluated as a universe unto itself, but if the works are chosen because of where they’ve come from, new criteria for considering them has been presented, which becomes more complicated as the world focuses on the massive revolutions taking place in Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Bahrain, Algeria, Morocco, Syria, and, lest we forget, Gaddafi’s heinous clowning in Libya. An exhibition with such earnest intentions as “The Future of Tradition the Tradition of Future” with works from countries that were allied with the Nazis in the Haus der Kunst, is slippery and muddied with questions that pull the exhibition’s artifacts into a maelstrom of questions of context, and away from the artifacts’ ability to stand independently. After all, Germany is not out of the woods on issues surrounding World War II. Victims of the war are still living, and much of the property, including confiscated art from Jewish families, has not been returned. It makes sense that all of Europe would prefer to put this history behind it, of course, but an exhibition of Islamic art which has been designed to encourage questions does not serve the purposes of presenting its artifacts free of context in this venue.

The 1910 and the 2010 exhibitions were both conceived as representations of art in the context of Muslim regions, and so while we can enjoy the pieces individually as masterful artistic expressions, in this milieu it is impossible to extract them from context. Shalem and Troelenberg state that the exhibition doesn’t seek a “neutral” approach to viewing the show, and how could it? How can viewers be asked to look “beyond sectarian or nationalistic tendencies” while viewing pieces that are titular reflections of their provenance? Sontag makes an excellent point that each piece of art should be evaluated as a universe unto itself, but if the works are chosen because of where they’ve come from, new criteria for considering them has been presented, which becomes more complicated as the world focuses on the massive revolutions taking place in Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Bahrain, Algeria, Morocco, Syria, and, lest we forget, Gaddafi’s heinous clowning in Libya. An exhibition with such earnest intentions as “The Future of Tradition the Tradition of Future” with works from countries that were allied with the Nazis in the Haus der Kunst, is slippery and muddied with questions that pull the exhibition’s artifacts into a maelstrom of questions of context, and away from the artifacts’ ability to stand independently. After all, Germany is not out of the woods on issues surrounding World War II. Victims of the war are still living, and much of the property, including confiscated art from Jewish families, has not been returned. It makes sense that all of Europe would prefer to put this history behind it, of course, but an exhibition of Islamic art which has been designed to encourage questions does not serve the purposes of presenting its artifacts free of context in this venue.

The Islamic world is often largely misunderstood in the Western world, and even as we try to understand from the perspective of contemporary society, the conflicts that are contagiously spreading through the North African-Middle Eastern region are only fueling Western curiosity. In regards to the exhibitions, an awful lot is asked of viewers to eliminate context from their minds when viewing “The Future of Tradition The Tradition of Future,” and the task becomes monumental when you consider the exhibition within the Haus der Kunst. As recognized by Koolhaas and Herzog, the halls of the Haus der Kunst still practically echo with the clapping of Nazi boots. And an exhibition there featuring art of Middle Eastern regions, many of which were allied with Nazi Germany, conjures a great many more questions beyond whether the artifacts are viewed in or out of context, because the history of the building is so domineering. In spite of movements to shift the purposes of the museum’s chilly corridors and austere marble halls, the intensity of the Nazi agenda to support nothing but classical art has been too well reflected and realized in the architecture of the building, which helps to call up Hitler’s alliances with Turkey and Egypt during the second World War—both countries are broadly represented in the exhibition.

Germany’s, and specifically the Nazi’s, history with Jews is world historical knowledge. And it is widely believed that pockets within the Arab world have close relationships to contemporary terrorism around the world. In addition, Munich has a long history of being a location in which these tensions have played out: the Dachau concentration camp is half an hour from Munich; at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, twelve Israeli athletes were killed by Arab terrorists, referred to as Black September; and on November 18, 2010, a date that coincided with the exhibition at The Haus der Kunst, German interior minister Thomas de Maiziere held a hastily called press conference in Berlin warning of known Jihadist terrorist attacks planned to take place in Germany. The exhibition at the Haus der Kunst should by no means have been viewed through the lens of terrorism, but perhaps it’s better to address uncomfortable relationships between Muslim regions and European society than to ask people to push them to the periphery. Nada Shabout, in another essay in the show catalog, says, “Politics has always played a central role in defining and redefining form and informing meaning in the visual production of Arab artists.” So, in regards to “The Future of Tradition, The Tradition of Future,” how can a thoughtful patron be expected not to extrapolate from the meaning of context and walk away free of thoughts of nationalisms?

In an e-mail interview, Shalem acknowledged that every curator who puts an exhibition into the Haus der Kunst must field questions about the history of the venue, and said, “This is true of any exhibition that is done there.” But an exhibition featuring the work of a New York punk scene pioneer like Patti Smith or of a Chinese political activist like Ai Weiwei has a unique relationship to the Haus der Kunst, one that transforms the museum’s original and now tired Draconian origins. The trauma inflicted against humanity during the Nazi era doesn’t seem entirely behind us. Many Germans would like to disregard the fallout, to move on and forget. Can we blame them?

In an e-mail interview, Shalem acknowledged that every curator who puts an exhibition into the Haus der Kunst must field questions about the history of the venue, and said, “This is true of any exhibition that is done there.” But an exhibition featuring the work of a New York punk scene pioneer like Patti Smith or of a Chinese political activist like Ai Weiwei has a unique relationship to the Haus der Kunst, one that transforms the museum’s original and now tired Draconian origins. The trauma inflicted against humanity during the Nazi era doesn’t seem entirely behind us. Many Germans would like to disregard the fallout, to move on and forget. Can we blame them?

But when within the walls of the Haus der Kunst, can we forget? An exhibition of art from regions that were in alliance with the Nazi party evokes something quite different in the House der Kunst. Reminiscent of a dark past, this something is not easily pushed to the periphery. Ω

Elizabeth Lopeman has written for American Craft Magazine, FiberArts, Bitch, Eugene Magazine, Drain Magazine.com, and various other magazines and websites. She currently lives and travels in Europe.