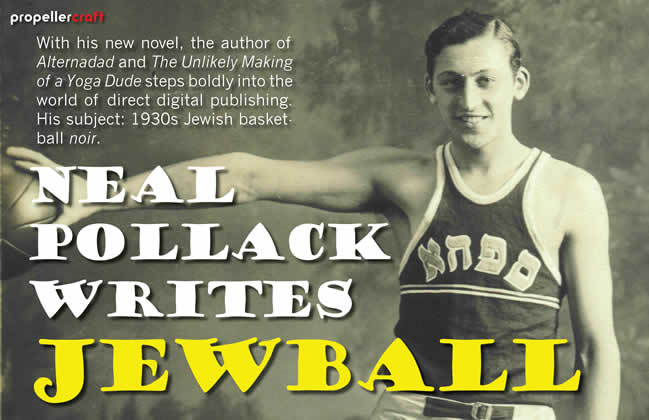

When Neal Pollack announced that he would be publishing his next book, Jewball, straight to the Kindle, the author whose first book was The Neal Pollack Anthology of American Literature: The Collected Writing of Neal Pollack did so with characteristic boldness: he said so in the New York Times Book Review. The author of Alternadad and Stretch: The Unlikely Making of a Yoga Dude kindly responded to questions on Jewish domination of early pro basketball, the pleasures of reading and writing noir, and the potentials of digital publishing in the era of e-readers. —Dan DeWeese

PROPELLER: When did you first become interested in writing about the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association basketball team? Was there something particular about the SPHA's (one of the more powerful American pro basketball teams of the 1930s) that made you feel there was a novel to be found there?

NEAL POLLACK: The idea for this book arrived as so many ideas do—during a conversation in a steam room in Utah. Several years ago, I was attending a retreat weekend for a Jewish organization called Reboot. The NBA playoffs were ongoing, and during a group schvitz, some of the guys started talking about the history of Jewish basketball. I'd never really heard about such a thing, but the more they talked, the more it sparked my imagination . Jews may not have invented the game, but they had a hell of a lot more to do with its development, I learned, than one might think. By the time I left the weekend, I knew that I’d have to write a book.

. Jews may not have invented the game, but they had a hell of a lot more to do with its development, I learned, than one might think. By the time I left the weekend, I knew that I’d have to write a book.

When I returned home, I started doing some research, and discovered the SPHA's, who were the most dominant basketball team, not just Jewish, but period, over a 15-year period spanning from the late 20s to the early 40s. They were really the forefathers of the modern game. Their coach and owner, Eddie Gottlieb, ended up founding the Philadelphia Warriors, and the SPHAs themselves became the Washington Generals, who were the Harlem Globetrotters' punching bags for decades. The team also appealed to me because they were from Philadelphia, a city where I lived for a couple of years. I have a pretty ambivalent relationship with Philly, but it's definitely a potent setting, full of grit and intrigue, that doesn’t get as much play as, say, Chicago or Boston. Jews in Philly rarely get talked about; New York dominates the conversation, for obvious reasons. Some of Jewball does take place in New York, but it’s definitely a Philly novel. I liked the idea of a whole team having a chip on its shoulder because of where it's from.

PROPELLER: There's obviously a genre we know as "historical fiction," but that phrase tends to suggest writers who approach the history aspect of their work with a degree of reverence. You've mined history more than once in your books, but definitely without the reverence. What do you think draws you to working with history and/or historical figures? And despite the fact that you bring a wicked sense of humor to your subjects, what kind of writing opportunities and challenges have you stumbled upon that wouldn’t be much different from those encountered by someone wanting to write straight historical fiction about, say, the Spanish Armada, life during the American Revolution, etc?

NEAL POLLACK: I'm attracted to stories with big scope and big characters. The times we live in are as dramatic as any other time in history, but it's hard to feel that way when you're immersed in the day to day. Many people do fiction in contemporary settings quite well, of course, but other than the occasional short story, it’s not how I want to write.

My previous fiction books had historical elements, but they were both straight-up satire. Not so with Jewball, which has comic elements but is a mostly straight hard-boiled narrative. Writing about Jewish basketball, I could have chosen any 1900s mini-period of its heyday—the late teens, the late 40s and early 50s—but as I did my research I was attracted to the late 30s, because Jewish basketball was at its height, coinciding with the height of German-American fascist patriotism, which was particularly strong in Pennsylvania. That history caught my attention and interest as much as the Jewish basketball stuff did. So my challenge was to try to integrate those two elements, which were obviously related but not directly, into a reasonably coherent plot.

My previous fiction books had historical elements, but they were both straight-up satire. Not so with Jewball, which has comic elements but is a mostly straight hard-boiled narrative. Writing about Jewish basketball, I could have chosen any 1900s mini-period of its heyday—the late teens, the late 40s and early 50s—but as I did my research I was attracted to the late 30s, because Jewish basketball was at its height, coinciding with the height of German-American fascist patriotism, which was particularly strong in Pennsylvania. That history caught my attention and interest as much as the Jewish basketball stuff did. So my challenge was to try to integrate those two elements, which were obviously related but not directly, into a reasonably coherent plot.

I wanted to get as many historical details right as possible, but the plot was much more important to me. In general, when it comes to historical fiction, American writers spend too much time respecting the struggles of the immigrant and not enough time telling a fun story. I tried to make Jewball feel, as much as possible, like a book that actually might have been written during that era, and to give the narrative an urgency and immediacy that historical fiction tends to lack.

PROPELLER: The idea of a book that feels like it might have been written during that era is compelling, in that it opens up so many questions about how one sets about that task. Are you referring to something stylistic—something about pre-WWII prose style—or something more structural in terms of what the novel's narrative voice knows and discusses and what it doesn't know or discuss? Or are you thinking more about general differences in the contract between writers and readers in those pre-television, pre-computers, pre-all-media-we-now-consider-standard decades?

NEAL POLLACK: Stylistically, I'm not sure if this is a 1930s book or not; there were different styles of writing back then as there are now. My main concern was to give the narrative a feeling of immediacy and urgency, for it to feel not like a history book, but instead like something pulpy and fun written on near-deadline by a guy desperate for money. Given my constant state of financial panic, that wasn’t too hard for me to accomplish. I didn't want to overwrite and overintellectualize the material. Sure, there's the occasional wink and/or nod to the present-day reader, but there aren't many, and you’d have to look pretty hard to find them.

PROPELLER: There are particular challenges to writing about physical skills—describing all the dancers' moves in a particular ballet tends to make the ballet boring and/or confusing to a reader, for instance, rather than capturing what the ballet actually looked or felt like. You've written about the body before, though, in Stretch: The Unlikely Making of a Yoga Dude, so you didn’t come to this challenge cold. Did you have strategies for how (or how much) you would describe basketball games or players' skills or moves in the book? Are there sportswriters (or any other writers) whose work has been helpful to you in this area—and how so?

NEAL POLLACK: I find writing about physical activity relatively easy. It's nice to have a subject matter that gives you so many active verbs with which to play. That's one of the hardest things about writing fiction—giving your characters something to actually do. Sportswriting wasn't much help, because most contemporary sportswriting is about LeBron James' “legacy,” and a lot of it gets gummed up by sentiment and melodrama. Older sportswriting tends to be slangy. Instead, for stylistic inspiration, I read old-school noir writers like Chandler, Goodis, Thompson, and Donald Westlake, not for subject matter, per se, but for style and mood and tone. I consider Jewball a noir novel that happens to have basketball as a partial subject matter, not a sports novel with some noir elements.

PROPELLER: What kind of things struck you when reading those writers with stylistic inspiration in mind? Any strategies, techniques, or particular decisions you found them using that struck you as interesting or illuminating? Were there a couple novels among that crew that stood out as particularly good examples?

NEAL POLLACK: I turned to them for mood. The sentences tend to be short and observant. A good noir novel has several paragraph or even page-length interludes that aren't much about the plot or characters, but rather about the feeling of a time or place. This is the stuff that sticks with me from books. Who killed whom means nothing, in the  end, but the feeling of life richly obversed goes on forever. The Blonde on the Street Corner by Goodis had a lot of influence early on, as did They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Later, as I wrote the book, I started reading Donald Westlake (and his psuedonym Richard Stark) who does those sorts of surprise expository grafs better than almost anyone.

end, but the feeling of life richly obversed goes on forever. The Blonde on the Street Corner by Goodis had a lot of influence early on, as did They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Later, as I wrote the book, I started reading Donald Westlake (and his psuedonym Richard Stark) who does those sorts of surprise expository grafs better than almost anyone.

PROPELLER: One challenge in writing noir in the twenty-first century seems to be that we're awash in so much visual media now, and the noir of television and, especially, the movies, has developed conventions that involve shadows, night, neon on wet pavement, etc.—a whole visual code for immediately signaling to the audience "This is noir!" But literary noir, because it's not visual in the same way, is a bit of a different creature. What kind of stories or experiences do you feel noir-on-the-page (for lack of a better term) offers readers that is distinct from noir-on-the-screen?

NEAL POLLACK: As I said above, the least interesting stuff about noir are the "mystery" elements, and the stylistic elements you mentioned are detective-fiction clichés. There’s often less of that in noir books than you might think. The Postman Always Rings Twice, one of the genre's best, barely has any nighttime scenes at all, for instance. Jewball contains no detectives. Cops rarely make an appearance. It's about a time and a place and a vibe. There is no mystery, just a story.

PROPELLER: You're self-publishing this book straight to Amazon's Kindle store. In your recent New York Times piece, you wrote that "for a writer like me, which is to say, most working writers—midcareer, midlist, middle-aged, more or less middlebrow, and somewhat Internet savvy—self-publishing seems to make a lot of sense at this point." Early on—which I guess means only like a year-and-half ago—I read a lot of prognosticators saying that books sold straight to the e-reader market would probably be mass-market fiction (or what some people call "airplane books") and possibly textbooks. That doesn’t seem to be how the economics of the e-book market are actually shaking out, though. How and when did you first start thinking, from an economic standpoint, about doing a straight-to-digital book? And was there a moment when the aesthetic experience of reading on a particular device—I’ll assume the Kindle—won you over?

NEAL POLLACK: When my latest corporate-published book advance was half of the last one, which was half of the one before that, I got the message. The traditional publishing model was great because you got paid a decent amount of money to work on a book, and, yes, you had to wait for it to come out, but at least there was a little credit in the bank account waiting for you. Now, though, you still have to work on the book, but for a lot less money, and for a publisher that is increasingly less interested in devoting resources to books that may or may not succeed. This isn't a mark on my publisher—I work with some great people there and they try very hard to make and sell good books for me—but the economics of the business don't favor a writer in my position. As for when I started enjoying the Kindle, I got a Kindle about 18 months ago, downloaded a book, read it, thought, this is okay, and then went back to reading regular books. But when I traveled with the Kindle for the first time, now that's when it won my heart. I'll never have to lug a shoulder bag full of books on a trip again. In that sense, it's one of the greatest inventions of all time.

NEAL POLLACK: When my latest corporate-published book advance was half of the last one, which was half of the one before that, I got the message. The traditional publishing model was great because you got paid a decent amount of money to work on a book, and, yes, you had to wait for it to come out, but at least there was a little credit in the bank account waiting for you. Now, though, you still have to work on the book, but for a lot less money, and for a publisher that is increasingly less interested in devoting resources to books that may or may not succeed. This isn't a mark on my publisher—I work with some great people there and they try very hard to make and sell good books for me—but the economics of the business don't favor a writer in my position. As for when I started enjoying the Kindle, I got a Kindle about 18 months ago, downloaded a book, read it, thought, this is okay, and then went back to reading regular books. But when I traveled with the Kindle for the first time, now that's when it won my heart. I'll never have to lug a shoulder bag full of books on a trip again. In that sense, it's one of the greatest inventions of all time.

PROPELLER: One of the nice things about writing is that it doesn't cost anything to create the product—you just sit down at the keyboard, which is far different from someone saying, "Dammit, I finally am going to start that restaurant I’ve been dreaming about! I’ll just go ahead and go $70,000 into debt to get the thing open, because I believe in this restaurant..." The economics of digital publishing don't require a huge financial risk. Are there other risks, though, or challenges you feel you're facing by using this publishing model with Jewball? And what kind of things are you doing to address those challenges?

NEAL POLLACK: I wouldn't say it doesn't require a huge financial risk. Yes, the capital outlay is pretty small for writing—I write my books on the same machine where I check my fantasy-baseball stats and watch my porn—but the outlay of time is tremendous. So if I put in hundreds or thousands of hours on Jewball and then only get 500 downloads (and, subsequently, less than two thousand dollars), then my per-hour rate is pretty laughable. But I can't think of it in those terms, at least not exclusively. Jewball is a book I've been dreaming about for years. I enjoyed writing it, and now I'm on the verge of trying to sell it digitally door-to-door. I'm going to work hard and send out hundreds of emails and Tweet and Facebook and Tumblr the sucker until my eyeballs bleed. If it flops, I've got no one to blame but myself, but at least I'll have the satisfaction of knowing that I went down on my own terms. Self-publishing is the future, or at least a big part of it, and I’m proud to be giving it a try. Ω