Mary Cappello’s fourth book, Swallow, appeared early this year. Her previous works of literary nonfiction are Awkward, Called Back, and Night Bloom. Cappello’s work departs from the usual conventions of nonfiction, taking an intense turn and using experience to make larger statements about the world. A former Fulbright lecturer at the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow, she currently teaches at the University of Rhode Island, and most recently was awarded a 2011 Guggenheim Fellowship in Nonfiction to work on a new book that she has tentatively titled In the Mood: Toward a Psychology of Atmosphere. I had the opportunity to chat with her outside of Seven Stars bakery in Providence, where the crutch of a diner at a neighboring table kept falling awkwardly into the conversation. —Sarah Kruse

PROPELLER: Your work focuses on topics many writers may never think of writing about. I’m thinking here of the unusual subject of Dr. Jackson’s Foreign Body Collection in Swallow and the investigation of the myriad ways awkwardness manifests in Awkward: A Detour. Would you consider yourself a writer of the unusual?

PROPELLER: Your work focuses on topics many writers may never think of writing about. I’m thinking here of the unusual subject of Dr. Jackson’s Foreign Body Collection in Swallow and the investigation of the myriad ways awkwardness manifests in Awkward: A Detour. Would you consider yourself a writer of the unusual?

MARY CAPPELLO: As a queer writer, it’s true that I am drawn to aspects of reality that run athwart, that are seemingly off-center, just out of view, but—and maybe here’s the crux—these things that I choose to write about are also everywhere apparent and pervasive but maybe just under-thought and over-looked. There is that principle, you know, both linguistic and psychoanalytic, that in order for something to cohere (linguistically or psychically), so much else needs to be barred or even rendered unintelligible. So, yes, the stakes of coherence are politically important to me. Some contemporary fiction writers whom I find inspiring for the way that they, almost in a Steinian tradition, bring the suppressed, unintelligible back into language are Dawn Raffel and Gary Lutz.

I’m keen to discover, too, how the un in unusual doesn’t simply negate the commonplace but newly illumines it. For example, I’m often asked the question: what is the strangest thing in the Chevalier Jackson collection that someone swallowed? At first glance, it’s obvious: the padlock is the most strange. Or the belt buckle. The wristwatch. The “Perfect Attendance” pin. Until I come to realize that the buttons are the most strange because they are the most commonplace. The ordinary, the banal, the habituated can be much more menacing than the presumably bizarre. What makes the buttons the strangest things in the collection is the realization that the oh so innocent button nearly killed a person.

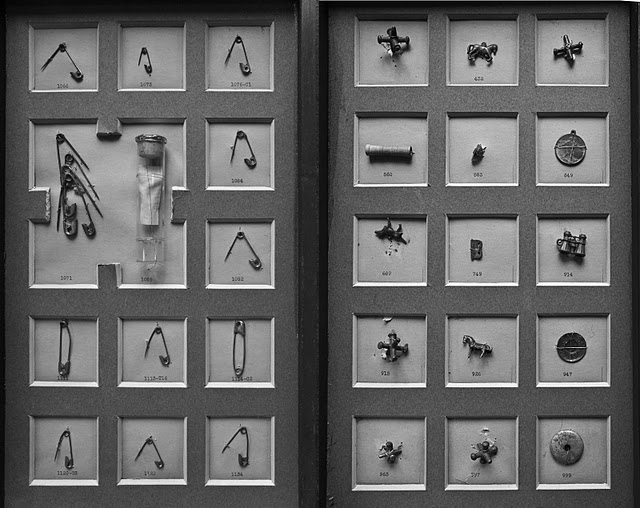

The cabinet of drawers containing the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection of things swallowed or inhaled, in Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum. From the Collection of the Mutter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Certainly we prefer that the strange be neatly sequestered or kept to one side until we realize, following Freud’s The Uncanny, that inside of everything homelike and familial lurks the ghostly double of the irreal and unfamiliar. This sort of approach to the “unusual” helps me, for example, in Swallow to ask questions that might seem otherwise impossible to ask about the normative and non-normative. For example, we might consider sword swallowing to be a profoundly strange activity but never question the practice of endoscopy in the medical realm. How on earth did it ever occur to someone to insert a metal tubular scope into a living, breathing, fellow human’s throat and airway? I think that’s a question worth asking, and, in turn, I bring a renewed sense of respect to the re-training of the autonomic nervous system required by a sword swallower, who, after all, is engaged in self-penetration rather than other-investigation.

PROPELLER: Awkwardness, foreign bodies: What first drew you to these subjects?

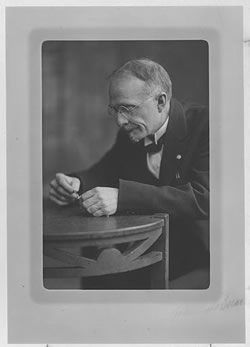

CAPELLO: I arrived at awkwardness via a long and circuitous route relative to living abroad at the time of the September 11th attacks, whereas the idea for Swallow simply appeared one day and changed me forever. You round a corner and the world gives you a gift: that’s what happened when I happened upon the foreign body collection in the Mutter Museum in 2006. I could hardly have imagined in that moment that one day I’d be co-curating the collection’s refurbished exhibit! The foreign body collection is an act of the imagination and it has incited the imaginations of many artists, not just me, and I’ll cite just a few: photographer, writer, and natural historian Rosamond Purcell; poets Kate Shapira and A.O.K. Wright; jeweler, artist, and assemblagist Lisa Wood; and filmmakers Kevin DiNovis and the Brothers Quay. So my being moved to write about the collection is hardly quirky. But one of the many ways that the collection’s quirkiness came to work on me had to do with its maker’s interest in de-emphasizing its weirdness. Because Chevalier Jackson was trying to make fellow physicians “foreign body conscious,” it was important to him that the collection of foreign bodies not be thought of as “curiosities.” He was, he claimed, trying to train his fellow physicians never to rule out the possibility of foreign body ingestion. “This isn’t a strange phenomenon,” he seems to want to say, “look, it happens every minute of every day.” To my mind, though, this doesn’t let Jackson off the hook of having made from the foreign bodies he extracted a cabinet of curiosities, for which there exists a long tradition and history. And once we start opening the drawers of his cabinet, we discover there is a great deal of off-limits knowledge that he wished to edit out of our encounter with the things.

Photographer Rosamond Purcell's photograph of two panels in the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection, one of which contains foreign body 1071, which Jackson considered his most difficult case. ©Rosamond Purcell, 2009.

PROPELLER: As a reader, the experience of Awkward seems something like a spiral, where the topic is never looked at directly, but rather from various degrees and many angles. Do you think of the book in this way?

CAPPELLO: Certainly in my classrooms, for example, and in pursuing an aesthetic of nonfiction in particular, I encourage my students not to look where they are trained to look in pursuit of truth-telling, unless of course they are willing to investigate that center rather than be seduced by it. I always recommend starting with language rather than with the ever nebulous but seductive “experience,” and with starting from a point or place that might not immediately recommend itself. I am very much convinced that a truth—or multiple truths—will out, if as writer/witnesses we allow ourselves to play about the margins of a subject, to look elsewhere. This requires un-training our trained attention, and sometimes un-learning what we’ve learned.

It’s gratifying to me that you experienced Awkward as a spiral since I’d assembled it as a series of concentric rings—well, that’s nearly a spiral! There are a few central themes that become more amplified, more voluble in the course of the book’s orchestration: learning how to breathe; becoming fully sentient; precocity; imbalance; discomfort; dissonance; facing or turning away; alternate arrangements of parts; learning how to be alone and learning how to be with others. I think of them as ever more voluble returns, as though the book is a vibration, and the circle of each of these themes widens or narrows depending on where it occurs in the book.

But I’d also like to mention that I called the book not a spiral but a “detour,” and I had very particular reasons for that. Awkward was meant to work as a discovery rather than a treatise or a proof. Sometimes the best discoveries are those arrived at by going off the anticipated path—discoveries require detours. A detour, to my mind, is a necessary wandering, a straying. But there’s something more precise at work as well. I called Awkward a detour because I was more interested in awkwardness as a language (mobile) than as a concept (fixed). This is a distinction I draw from French psychoanalyst JB Pontalis’ book, Windows, where he suggests that if you enter something as a language, you find it wants and needs to travel, and it won’t allow you to come to the point, but to wander toward multiple points, arrived at from multiple directions. Pontalis talks about this need to detour and wander in the context of psychotherapy: the circuitous non-narrative routes a person must take in order to achieve psychological insight and real change in the “talk therapy” that constitutes a psychoanalytic relation. My own indulgence of detours isn’t meant to be therapeutic but to be playfully contemplative: to open up interpretive byways in awkwardness’ name.

PROPELLER: What went into the process of organization in Awkward to create this effect? And is it at all a kind of oblique kind of sense making?

PROPELLER: What went into the process of organization in Awkward to create this effect? And is it at all a kind of oblique kind of sense making?

CAPPELLO: The organizational process entailed a piecing together relative to collage work. Juxtaposing parts I’d composed separately (Joseph Cornell’s carefully placed forms and objects inside his startling and beautiful boxes were a big inspiration here—something I cannot claim but only try to aspire to). I’m not sure I’d call it an “oblique” form of sense-making but rather a poetic—as in associational—form of sense-making. The emphasis then is on placement, and sometimes to my great pleasure, on incompatibility of parts. Organizationally, it requires attending to apposition rather than opposition: opposition cancels, apposition makes apparent; opposition negates, apposition fosters and opens, etc. Importantly, the organization of Awkward was helped along by an editor too. Erika Goldman at Bellevue Literary Press and I worked together on my original organizational strategy, placing and re-placing parts after the quilt had been assembled.

PROPELLER: In much of your work you seem to be pushing the limits of experience to a point where through intensity, experience becomes lyrical. Could you address the role of the lyric in your work?

CAPPELLO: I’d like to go at this from two points of view: lyricism as form of musicality, and lyricism as an alternative to sentimentality and not to be confused with same.

Tone was extremely important to me in Called Back, and I wanted the book to serve as a tonal antidote to the voice of the stuff that is otherwise available to us in cancer guides, and cancer magazines, and cancer websites, and cancer pamphlets. I was often disturbed and depressed by the tone of materials I was given to read or needed to read as though all the culture could offer me were forms of muzak, or infantilizing ditties, or moralizing instruction manuals that made me feel responsible for the cancer inside me. And the voices of all of these different kinds of texts created a surround, and it wasn’t one I could possibly rely on to hold me, and the voices, their tones, created an idea of a listener, and I didn’t like the kind of listener they were asking me to be. What if the tone were one of irony? What if the tone were truly warm? What if the tone had revery in it? Could it be passionate or furious or smart? Could I expect a tonal range, a tone that could make me laugh and cry? Could it embody a feeling mind? I went at the writing with tonal variance as an imperative.

From another point of view relative to lyricism, there was the matter of making that which was harrowing into a work of art without consequently taming it. I found a generous reader in writer Jane Lazarre, whose own book on breast cancer (Wet Earth and Dreams) is singular, and lyrical too. Jane commented that I had made poetry out of this horrific experience without sacrificing any of the gory details or the sense of the dehumanizing of it all, as she put it, while making it beautiful, at times so funny, or “funny-awful” that she laughed out loud in parts. How might we reconcile poetry with something as brutally horrifying as cancer? This is a question that I find important to engage. It requires that we distinguish between lyricism and sentimentality. First and foremost, inside of illness, reality is altered and you’re in an altered state. That’s where poetry comes in: poetry at its best induces altered states and represents altered states. Illness is one such altered state. It would be a narrow understanding of poetry that couldn’t imagine illness as a subject. I don’t think that art and the terrifying and terrible are mutually exclusive or even opposed. Moreover, I’m always after a beauty un-opposed to ugliness. A disruptive beauty. I like to quote the Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam, “Life is both terrifying and beautiful.” Can a book achieve an embodied sublime? That was a challenge I gave myself in Called Back.

PROPELLER: In terms of the lyric and language, it seems you have a unique way of looking at language and through language. Throughout Awkward, you continually examine your relationship to language, others people’s relationship to language, and the relationship of people to one another through language. In terms of the lyricism of the book, what work does the playfulness of looking at a word or unraveling a phrase do for you as a writer?

CAPPELLO: I think of language as runic in this sense: I’m convinced that language holds answers that seem otherwise impossible to access, if only we are willing to play inside of it. If you reach an impasse in writing (or in life, for that matter), I say turn to the language; let it teach you; follow it.

CAPPELLO: I think of language as runic in this sense: I’m convinced that language holds answers that seem otherwise impossible to access, if only we are willing to play inside of it. If you reach an impasse in writing (or in life, for that matter), I say turn to the language; let it teach you; follow it.

How are you thinking today, Sarah? I suspect no one has asked you that, because no one has asked me that either, because it’s not a question that is colloquially available in the way that “how are you feeling” is. Why not? And what could it possibly mean to ask how a person is thinking? Prepositions are especially fun to play with this way. They’re so powerful! An entire writing practice would have to change if, for example, I gave myself the imperative to write from x, y, or z, rather than about it. Or for. To. Or across. Against. Or, remembering Trinh Minh-ha’s aesthetic principle in Reassemblage, I might try to write nearby.

Language is of paramount importance to me. But isn’t that like a painter saying that she takes seriously color, light, and line? Yet very few writers, aside from poets, seem interested in changing the language. I prefer to read work that requires me to attend to language differently. Perhaps it goes without saying that I can never get enough of writers like Emily Dickinson and Gertrude Stein. Word auras, and the shapes of sentences. Rhythms. That’s what I read for.

The language we have available to us on any particular subject—from disease to global warming, from love to war—determines the conditions of possibility for understanding, solving, treating, or transforming those same realities. In Called Back, I wondered, what if instead of saying, ‘I have breast cancer,’ I said I had EPM—Environmental Pollutant Marker, or Environmental Pollutant Mangler? Or PPP—Plastic Polymer Perverter. Our words aren’t merely add-ons to already existent realities; they’re the very shapers of the real as we know it. Words aren’t things that we can take or leave. Great writers, according to Deleuze, inhabit their native language like a foreigner. Making language stutter. That’s a state worth courting.

PROPELLER: I noticed in reading Awkward somewhat of a poetic statement in regard to tact and poetry. You say, “Tact, unlike the poetry of Sciascia’s perfect images, is a right use of language that is prescribed; poetry is a right use of language that no one could expect but once it has come into being strikes one as indubitable.” Are there moments within awkwardness that achieve a lyricism that seems “right,” as in poetry?

CAPPELLO: What a wonderful question. I’m certain there is, but of course that moment is often confused with grace. I cannot name it—that moment, where and when it occurs, but it’s worth looking out for. Maybe it’s most immanent in the work of high comedic slapstick art—Charlie Chaplin, Lucille Ball; or in that place where our being is most individuate: What’s awkward about anyone is also what is beautiful about them, all that is attributable to them and to no one else.

PROPELLER: Shifting the subject to your most recent book, Swallow, I was struck how early on you refer to the foreign bodies as petits objets. This has a Lacanian overtone, connecting to the object petit a, or that little obscure object of desire. Was the idea of desire and object, and what objects become endowed with through us, something you were thinking about when working on Swallow?

CAPPELLO: Absolutely! Three seemingly simple questions orient my opening of the foreign body drawers: who was that man—Chevalier Jackson? How does someone swallow that? And what are these things? I was fascinated by the shifting status of the things, the way in which they could be inflected with a different order of fetishistic meaning depending on where they were located: for example, a jack in a thorax is no longer really a jack. A threat to the body via the object world; a thing out of place; a bit of matter that is part body. Once extracted by Jackson, it assumes yet another cast—that has to do with a complex entwining of his own deftness combined with a need for mastery. This is followed by his stowing the object in his cabinet—insisting that he get to keep it. Now it becomes part of a vast cosmology of swallowed things, but what sort of universe is this? Then it also becomes subject to our consumption of it and valuation of it as we stand in awe before the cabinet, fascinated and benumbed.

CAPPELLO: Absolutely! Three seemingly simple questions orient my opening of the foreign body drawers: who was that man—Chevalier Jackson? How does someone swallow that? And what are these things? I was fascinated by the shifting status of the things, the way in which they could be inflected with a different order of fetishistic meaning depending on where they were located: for example, a jack in a thorax is no longer really a jack. A threat to the body via the object world; a thing out of place; a bit of matter that is part body. Once extracted by Jackson, it assumes yet another cast—that has to do with a complex entwining of his own deftness combined with a need for mastery. This is followed by his stowing the object in his cabinet—insisting that he get to keep it. Now it becomes part of a vast cosmology of swallowed things, but what sort of universe is this? Then it also becomes subject to our consumption of it and valuation of it as we stand in awe before the cabinet, fascinated and benumbed.

My work with the objects as such isn’t so much influenced by Lacan as by object relations theory, notions of incorporation, and the idea of objects being more sentient to children than they are to adults. In an earlier version of the book, I included an array of what I called “object lessons,” but I agreed to edit those out of the final version because discursively they represented a radical departure from the rest of the book. Here’s an example of one for fun: All objects rest in a lowing gold. All lowing knows of an object told. All objects meet in a shelf-life red. All objects start to a rigid dread. All objects edge toward a stop sign bled. All reds resume in a gaslight fed. All greens rejoice in a sequin sped. All things object in a voiceless head.

PROPELLER: Does the idea of the cabinet, categorization, and organization relate to this idea of desire, and how are you working with or against the idea or organization?

CAPPELLO: I’m trying to understand how Jackson’s steadfast arrangements morph into a form of derangement. This is not in any way to diminish the enormity of Jackson’s contribution to medicine, the difference he made in the lives of thousands of people, his singular set of skills, and his inimitable genius. Where his collection was concerned, he documented it tirelessly, as though trying to find the form (usually by way of a grid or inventory or list) that could best contain it. To me, this is where some of the interest in Jackson’s psychology enters in, because he went to great lengths to try to control foreign body ingestion (after all, he was trying to treat it), but the fact is that, so long as we have mouths, it will not be eradicated, and so long as we have psyches, baffling forms of non-nutritive ingestion will persist. Every time Jackson attempts to secure a foreign body inside one of his frames, the collection threatens to explode with waywardness: foreign bodies wander (that’s part of what’s so weird and fascinating about them); the physiology of the human swallow is fraught with the possibility of freak accident; and human desire is infinitely complex. All of the ordering systems in the world can’t tamp that down.

So many different kinds of lists accompany the foreign body collection reflective of Jackson's attempts to translate the collection into forms of useful knowledge, but also, to my mind, to tame the foreign body collection of its wildness—even as the lists, of course, create their own form of madness. The human viscera in the light of foreign bodies seem to stretch thus testing the limits of psychic and bodily contain-ability; Jackson’s cabinet, in turn, beautifully orders what it cannot contain.

So many different kinds of lists accompany the foreign body collection reflective of Jackson's attempts to translate the collection into forms of useful knowledge, but also, to my mind, to tame the foreign body collection of its wildness—even as the lists, of course, create their own form of madness. The human viscera in the light of foreign bodies seem to stretch thus testing the limits of psychic and bodily contain-ability; Jackson’s cabinet, in turn, beautifully orders what it cannot contain.

PROPELLER: On page 23 you mention how you began to feel “the tug of narrative.” What is it in particular that struck you with narrative potential in these objects? Was it the specific human stories that lie within each object? Or a larger narrative of what it is to be human that the objects speak to? As a writer, what does that narrative pull entail for you?

CAPPELLO: This is a very rich question, and I hope that my answer can give you a sense of the tantalizing pendulum swing that is involved in opening the foreign body collection and discovering ‘story’ in the case notes that accompany each object (which are mostly to be found in the archives of the National Library of Medicine). First of all, I think it’s worth noting that the narratives compete with the objects as non-narrative assemblage. My book, consequently, in its attempt to address this tension, is both narrative and non-, and I organized its chapters to open like a set of contiguous drawers. (For my own part, I like to think of essays as workshops for making, breaking, and reinventing order, and Swallow is very much an essaying). Narrative case studies; non-narrative assemblage: on first approaching the foreign body cabinet, I was overcome by a sense of absent presences. It felt to me that I was entering a haunted house. The bodies of the people from whom the foreign bodies hailed were out of view even as the objects were strangely indicative of them as a trace. The objects are menacingly mute. I did consider one of my charges to be the re-attachment of the things to their owners, and that the narrative was then in some sense, from the outset, a kind of ghost story. Once inside the case studies, the allure of mystery is tempered by realities that are harder to take: there we find social histories of hunger, self- and other-directed violence, and more. If you follow a hatpin to its end, you must also meet with the interesting terms of its cultural history, which isn’t entirely severable from the personal history of the person who accidently or purposely ingested it.

There was one case in particular that felt very ghosted to me, and whose reconstitution I felt responsible for. (By the way, by reconstitution, I do not mean to suggest correction, solving, or resolving, but, yes, perhaps the need for narration as an ethical charge). I had already drafted a great deal of the book, and I certainly hadn’t expected to find more material at that point. But Chevalier Jackson lived into his 90s and was a pack rat, so it’s probably impossible to uncover every scrap of ephemera relative to his life and work, unless one were to devote a lifetime to the project (which I did not care to do). I was looking through materials that were found in the barn at Jackson’s homestead in Schwenksville, PA, when I happened upon a case study that I thought I should copy. It told of a boy who had swallowed a half dollar but who had not been believed by the doctors his father consulted. By the time he’d been treated by Jackson, he was terminally ill, and had suffered the effects of the coin for most of his young life from age 4 to 10. He was a patient who was, sadly, beyond Chevalier Jackson’s care. When I returned home from this archive, I was engaged in the task of combing through textbooks authored by Jackson to find images that I could use in my book (the reason I was even doing this was that a major repository of his images had closed due to funding problems, so I had to look elsewhere). Leafing through these books, I happened upon images of an anonymous, emaciated boy, his eyes blacked out, his frailty exposed. I felt that I knew this boy. I’d seen this image in a number of other contexts in the course of my research, but only then did I put the textbook photographs together with the case study that had been found in the barn. Now I matched them up—it was obvious that I had found the boy and could identify him—and I saw that there were details of the case that Jackson had not told. I felt, literally, the boy’s presence, like he was inhabiting my attic study with me. After many, many decades, the boy materializes, and I realized then that I must close the book with his story. It was that magical, and clear.

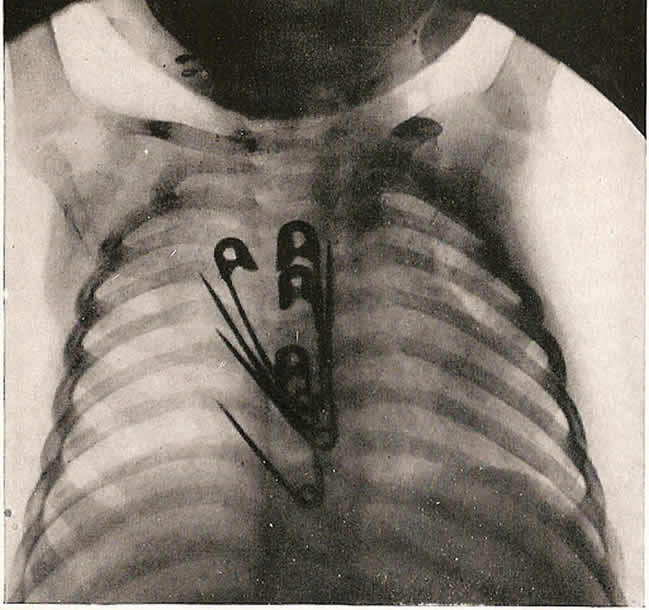

An x-ray revealing the appallingly daunting scale of Case #1071—what Jackson described as his most difficult case—in which four large, stiff, interlocked safety pins were impacted in the esophagus of a nine month old baby and bound together with an entangled mass of wool. Details in the case that Jackson does not report suggest that the ingestion of the pins was neither accidental nor the result of “carelessness” per se. The baby’s older sister apparently “fed” the child the pins. From the Collection of the Mutter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

I’ll close with one more example of narrative pull, which, as you can see, is hardly cut and dried. (I need note too that I have only opened a fraction of the foreign body drawers. I believe the cabinet awaits novelists and filmmakers galore). There was a case in the National Library of Medicine that I became particularly attached to, in part because of, again, the indicative details that Jackson left out in his reporting of it, and in part because of photographs of the patient that were attached to the case. The boy, Joseph B., had been “fed” scores of non-nutritive items by a deranged babysitter when he was 9 months old. Among these were safety pins that lay open in the baby’s esophagus. Chevalier Jackson and his team saved the baby’s life, and over the years, the boy’s family evidently sent Jackson pictures of the boy as he grew older to show Jackson that he continued to thrive. When I was writing this chapter, of course I had questions: how had the boy fared in later life, given his exposure to upwards of 30 x-rays as a baby and given this infanthood trauma? What had the babysitter been “thinking”? Who was the babysitter and what had happened to her? I tried to discover if the boy was still alive (the case dated back to the 1920s) but was not able to find him—he had a common surname, and had lived in a densely populated area of Pennsylvania. I hoped that maybe someone would recognize the boy by way of the image that appeared in the book. Recently, I received a letter from a woman who happened upon an excerpt of Swallow in ProTo magazine, a journal affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital, where her husband had been treated for cancer. An x-ray of a baby with pins in his esophagus that accompanied the article reminded her of her father’s case, and she wrote to ask if this could be him. I thus was found by the daughter of the baby who’d been fed the items by the babysitter. Her father is deceased, but she and I and her mother have struck up an extraordinary correspondence that I hope to write about. On September 10th we will meet in person at the Mutter Museum where I will open the drawer with their father’s foreign bodies in it for them to see.

Where does this leave us in terms of the pull of narrative? Well, I learned from my new friends that the family never took the case to the police, but instead to the parish priest, and that it was “left at the parish door.” And that the family would see the woman who’d perpetrated this strange act in the marketplace from time to time, and their blood would run cold. One kind of inquiring mind would consider that she may or might or must have done this to other children in her care. That there might be cold case files available in this city of children who died of unknown causes that could be linked to her. Could there be a way for us to identify her, and if so, would it help us to understand more clearly the condition from which she suffered? How did her own life come to a close? Much as I would definitely be interested in finding answers to these questions, I’m just as much if not more interested in the correspondence that has emerged between me and the patient’s family. I’m interested in the stories they want to tell me, and the stories they told themselves these many years. I’m interested in the fact that relationships are forged in a far contemporary moment from the fact of a foreign body thing stowed in an eccentric genius’ cabinet of curiosities. I do think I’ll want to make an essay out of that. A writer only has one life, and so many narrative choices. Ω

One of several pictures of Joseph B______, the nine-month old victim of Case 1173, as a boy. The photos were sent, like thank you notes, to Chevalier Jackson by Joseph’s family as evidence of the boy’s continued life. Chevalier Jackson Papers, 1890-1964, MS C 292, Modern Manuscripts Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland

One of several pictures of Joseph B______, the nine-month old victim of Case 1173, as a boy. The photos were sent, like thank you notes, to Chevalier Jackson by Joseph’s family as evidence of the boy’s continued life. Chevalier Jackson Papers, 1890-1964, MS C 292, Modern Manuscripts Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland