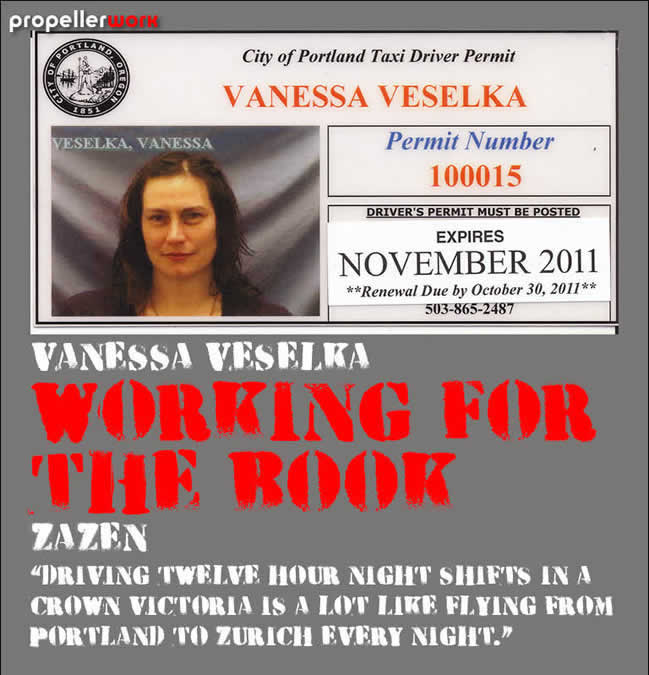

In this issue, we asked two debut writers to speak about how they made ends meet while working on their books. Vanessa Veselka's debut novel, Zazen (Red Lemonade), came out in July. "She’s penned a dystopic romp through a ravaged America. It’s the best kind of imagined world because it’s one ripe with recognizable humanness amidst unpredictable narrative bends," wrote The Rumpus's Joshua Mohr about Zazen. Between further dystopic romps promoting Zazen while continuing to make ends meet, Veselka answered a few questions about the period she spent behind the wheel of a cab.

PROPELLER: How and why did you first start thinking about driving a cab?

VANESSA VESELKA: I got the job through my friend Kirsten. She drives nights for Radiocab and has for the past six years. There's a whole crew of goth musicians and drunkards and disturbed vets down there. I liked them. They were my favorite part of the job. I liked the dispatchers and the call-takers too. The whole world of the place was so insular and particular in one way and so diverse in another, it was addictive.

PROPELLER: What about cabbing worked for you? How long did you drive?

VESELKA: I drove cab for a little under a year but I worked a lot in that time, 40-60 hours a week. I still keep my permit up and will. As one cabbie said to me, "This is the greatest job in the world. I quit every single night and can get hired the next day." There's something to that, but the job was rough for me. I hate to drive, for one, and I am a morning person and a mother. Driving twelve hour night shifts in a Crown Victoria is a lot like flying from Portland to Zurich every night. The money could be very rough. The leases were high and there are nights you come home with zero, or have to pay. Flipping your schedule around twice a week will take years off your life. People say, "Oh, well, it must be great material for writing, all those people you meet. What a great place for a writer!" and you want to kill them. A great place for a writer is sitting down and writing. And that was my problem, ultimately: I wasn't able to write. I was exhausted all the time and still broke. But the cool part was that there is definite brotherhood of cab drivers all around the world and I had a temporary pass to see some of it. I'll write about that someday. I was approached by Willamette Week during my first week driving and asked if I wanted to be their new "Night Cabbie." I ended up turning it down because I didn't want to write anecdotally about what I saw there. There is something vast and strange about the job that is tied to both American and international culture in such a particular way—I want to write about that. And I loved the cabbies.

PROPELLER: How do you feel the reality of cabbing is most different from the way we see it depicted in books or on the screen?

VESELKA: Are you talking to me? Had to get that out of the way.

VESELKA: Are you talking to me? Had to get that out of the way.

WeIl, I think ideas about cabbies fall into one of two categories: "Taxi" or Taxi Driver, which is to say Alex Rieger or Travis Bickle. I have to say both are true. It really surprised me when I started working how much the writers of "Taxi" nailed the garage scene. It's stereotypes and TV lines, but there's a ring that's true. I loved hanging out at the garage and listening to cabbies and dispatchers and supervisors talk. They're all natural storytellers and truly strange and unique people. I think we've bleached out a lot of the bizarre in our culture, so it feels like life when you're around people who aren't so pinned down.

On the other hand, there are Bickles out there, too. A lot of vets came back from Vietnam with severe PTSD and couldn't deal with people, couldn't get jobs, couldn't sleep at night—so what did they do? Start a cab company. No boss. Just you and your gun driving around the DMZ ready for anything. I picked up a woman once who got in the cab and said, "Oh, thank God. The last guy who picked me up was brushing his teeth and had an 8-inch hunting knife on the dash and said he would 'take care' of anyone who was bothering me." The next thing she said was, "Should I let somebody at the company know?" Only in cab driving is that a legitimate question.

But the thing that surprised me was that the money was so bad. People think of cabbies making bank, but they don't. And the crazy thing is they don't know that they don't. Maybe if you own your cab, but for most of the lease drivers, they'd make more doing dishes at Por Que No?. But you can't tell them that. "Dude, I don't know about you but I make 200 dollars every night!"

Except on the nights when you don't. And even if you do, do the math. You pick up your cab at 4pm for a twelve hour shift. Say you work ten hours. You make $200, so that's $20 an hour. You have to show taxes to keep your permit and the credit slips keep you from lying too hard. It's 30% for independent contractors. So you walk with $160. That's $16 an hour. But there's always that one night that you don't hit the $200 or you have to work the full twelve hours for a couple of shifts. Basically it's an $8-$12 an hour job and no one wants to admit it. And that's without factoring in the costs of living on a night shift. So why do night cabbies do it? Same as strippers—for the freedom, not the money. These are people who absolutely hate the idea of working for other people. They're natural gamblers. They remember the $400 night and forget the other three nights that month where they went home with nothing.

It's a different kind of glory. Ω