Europe Endless

Europe Endless

Albers in America

By Elizabeth Lopeman

By Elizabeth Lopeman

“Albers was a beautiful teacher and an impossible person…He wasn’t easy to talk to, and I found his criticism so excruciating and so devastating that I never asked for it. Years later, though, I am still learning what he taught me, because what he taught had to do with the entire visual world…I consider Albers the most important teacher I’ve ever had, and I’m sure he considers me one of his poorest students.” —Robert Rauschenberg on Joseph Albers

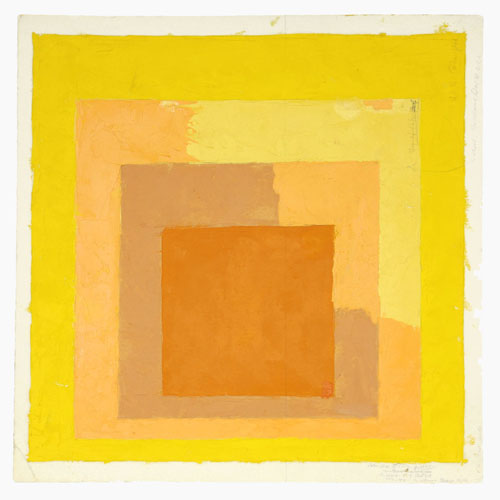

hrough October 14, the Morgan Library in New York is exhibiting “Joseph Albers in America: Painting on Paper,” a collection of oil paintings on paper that were mostly studies for Albers’ extensive series, “Homage to the Square.” Albers produced his first “Homage to the Square” painting in 1950, the year he arrived as Visiting Critic at Yale, which was shortly followed by a position there as the Chairman of the Department of Design. The last in the series was completed in 1976, the year of his death—he was 88. I was lucky to have seen the exhibition on its first stop of the tour at the Pinokothek der Moderne in Munich before it continued on to Centre Pompidou, Paris, and then to Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, before arriving in the United States.

hrough October 14, the Morgan Library in New York is exhibiting “Joseph Albers in America: Painting on Paper,” a collection of oil paintings on paper that were mostly studies for Albers’ extensive series, “Homage to the Square.” Albers produced his first “Homage to the Square” painting in 1950, the year he arrived as Visiting Critic at Yale, which was shortly followed by a position there as the Chairman of the Department of Design. The last in the series was completed in 1976, the year of his death—he was 88. I was lucky to have seen the exhibition on its first stop of the tour at the Pinokothek der Moderne in Munich before it continued on to Centre Pompidou, Paris, and then to Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, before arriving in the United States.

The “Homage to the Square” series includes over a thousand paintings—squares of carefully considered colors, nested three, sometimes four, deep with a border of white gesso on 30x30 cm or 120x120 cm pieces of Masonite. In addition there are numerous screen prints and lithographs in the series. Albers took meticulous notes on the interactions of colors with the understanding, or belief, that, in his words, “In visual perception a color is almost never seen as it really is. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art. In order to use color effectively it is necessary to recognize that color deceives continually.” He rejected the paintbrush, squeezing paint directly from the manufacturer’s tube before spreading it in thin layers with a knife, and so accumulated the most impressive contribution to color theory in the modern world by discovering what happens when four different shades of red are arranged within a square format from light to dark, or dark to light. Or yellows with blues and greens, etc. He never tired of noticing “the discrepancy between the physical fact and the psychological effect.”

Albers taught art at Yale, Black Mountain College, and at the Bauhaus after completing his studies there. Artists who either worked with or studied under Albers make up a monumental list. Klee and Kandinsky, Gropius, and Mies Van der Rohe were a few of the teachers at the Bauhaus. De Kooning, Franz Kline, and Buckminster Fuller worked alongside Albers at Black Mountain College and the list of his students includes Rauschenberg, Twombly, Eva Hesse, John Chamberlain, and the inimitable Neil Welliver. Though Albers had access to the bulk of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, his seriousness about his own work prevented him from spending much time with any of them outside of the classrooms or faculty meetings. He was probably most admiring of Klee, whom he met at the Bauhaus and who shared his interest in color theory, but Albers rejected the idea of expressionism and hated the term. In the Jeannine Fiedler and Peter Feierabend book Bauhaus, when asked about the already-famous Robert Rauschenberg, Albers is reported to have said that he couldn’t be expected to remember all the names of his former pupils.

His father was a craftsman—a house painter and a decorator who, in typical German form, taught his son the importance of discipline within his craft, which Joseph went on to exemplify for his students throughout his career. “Homage to the Square” was a fete of discipline not only in the creation but, possibly principally, in the extensive cataloguing of colors and their visual effects on each other. Albers said his father taught him to paint a door from the middle to the edges to avoid dragging a cuff in the paint, and he credits his father for this technical approach to “Homage.” Art and design programs throughout the world assign Interaction of Color, his first book, which was published in 1963 and is a seminal work of prodigious proportions. In 1971 he became the first ever living artist to be honored with a solo retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Albers was the longest working teacher at the Bauhaus and one of the few who closed down the school when Nazi aggression made its operation untenable. Joseph had married Annelise Fleischmann, a fiber-arts student at the Bauhaus, who came from a prominent publishing family from Berlin that had converted from Judaism to Christianity. Regardless of the conversion, under the Nuremburg Laws Anni Albers was Jewish, and getting out of Germany became paramount for the couple. In 1933 the newly established Black Mountain College in North Carolina offered Joseph a teaching job. Eddie Warburg, a Jewish patron of the arts who arranged Albers’ position, was ecstatic, and wrote to a Alfred H. Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), “With Albers over here we have the nucleus of an American Bauhaus!”

Anni taught fiber arts at Black Mountain College, and the couple enjoyed being in America and experiencing the exuberance and friendliness of the people, especially. They traveled on numerous occasions to Mexico, where they were both influenced by the exotic and clearly non-European colors and textures. Anni became famous internationally for her textile designs, fabrics, and wallhangings, as well as for prints she made later in her career, and for her book On Weaving. She was indubitably Joseph’s strongest supporter, and thirteen years after his death, in 1989, when the two Germanys reunited, Anni received considerable compensation for property that belonged to her family prior to the war, with which she established the Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut. The foundation funds exhibitions and publications, outreach art education for children, and has a residency program by invitation.

The exhibition now at the Morgan Library is like a precious little window into the mind of a modern master. The paper is stained through and through with oil, and the paints have chicken scratches in pencil etched into them. They’re repetitive in form and frequently in color, and you can touch on one and then another with your intellectual light either on or off. I recommend on first, and then a walk through with it off. Or vice versa. It’s a treat to have exposure to the relatively messy process of someone whose works came so close to perfection, and certainly to someone with such far reaching impact and influence. “Though technique for me is a big word, I never have taught how to paint,” said Albers. “All my doing was to make people to see."

*Photo of Albers color study courtesy of Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop

Elizabeth Lopeman has written for Sculpture Magazine, American Craft Magazine, FiberArts, Bitch, Eugene Magazine, Drain Magazine.com, and various other magazines and websites. She currently lives and works in Munich.

Elizabeth Lopeman has written for Sculpture Magazine, American Craft Magazine, FiberArts, Bitch, Eugene Magazine, Drain Magazine.com, and various other magazines and websites. She currently lives and works in Munich.