Craft

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

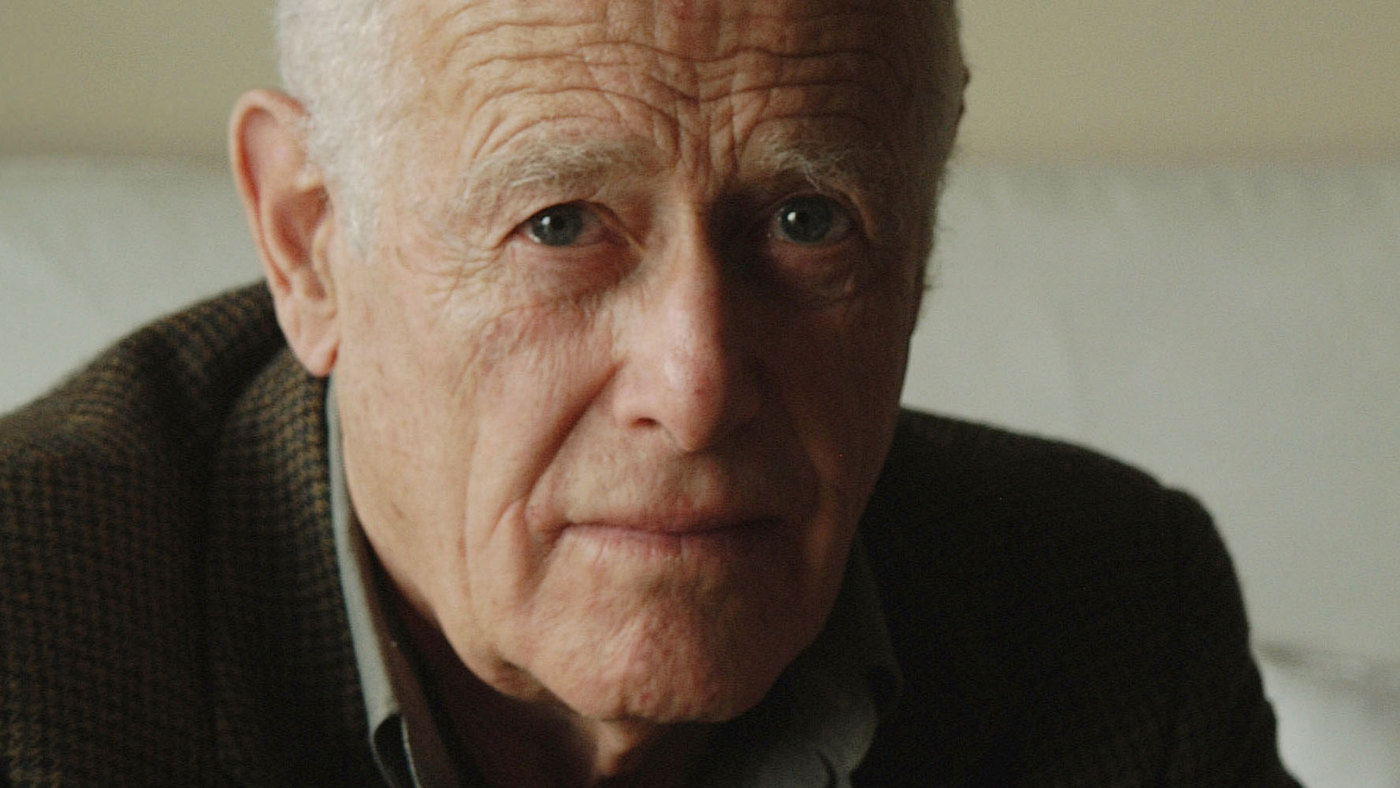

JAMES SALTER’S first novel, The Hunters, was published in 1956, when he was a fighter pilot serving in the Korean War. Over the course of the ensuing decades he has published five more novels, two story collections, the memoir Burning the Days, and Life is Meals, a “bedside book” co-authored with his wife, journalist and playwright Kay Eldredge Salter, that includes recipes and culinary hints, observations, and anecdotes. His work has been recognized with the PEN/Faulkner Award (for Dusk and Other Stories) the 2012 PEN/Malamud Award, and the inaugural Windham Campbell Prize, among many other laurels and notes of admiration. Salter’s latest novel, All That Is, was published in April. It follows the character Philip Bowman from his service in World War II through his career as an editor at a small publishing house in New York, and includes episodes and relationships that span the Atlantic and the second half of the 20th century.

We had planned to meet at a restaurant in Manhattan, but Salter had broken his leg a couple days before the interview, so Kay Salter kindly showed us to the Salters’ small sublet apartment near the United Nations building. Despite his injury, Salter was generous and uncomplaining throughout an hour and a half of questions over coffee and croissants. —Dan DeWeese

Dan DeWeese: Did you know from the beginning that you wanted All That Is to have the kind of scope it has, or did this project change over the time you worked on it?

James Salter: I don’t think the scope, that is to say the arc of the book, changed. But the way it proceeded changed a little bit, with events and people mostly moving in and out, well-defined but perhaps not reappearing. I didn’t plan it that way. It just started to happen, so I kept doing it, it seemed that might be interesting. And that eventually became the general—I don’t want to say “structure,” but maybe “architecture” is a better word—the general tone of the book. But I knew it was going to take up the same span of my own life. I wanted it to start with the end of the second war and go up to, I don’t know, somewhere around now—nothing precise. And the events were all along that chronological line. But there were many things that I thought that would be in the book that I didn’t put in, and vice versa.

DeWeese: When I’m reading it, you seem very free, in a good way, about a willingness to have episodes in the book that are well-drawn…I’m just thinking about myself as a writer, I would sometimes have a concern that I need to follow up on those in some kind of really orderly way. But a lot of this book’s power seems to come from a certain kind of freedom from those kinds of concerns.

Salter: Yes, that was what I was trying to say when I answered the previous question. The boundaries of the book seem a little amorphous. It’s kind of a dream, and things are real, and they might be on the edge of it—it’s not the usual feeling. Naturally, some readers don’t like that. I mean, I’ve heard that, “Why, why, why? What happened to that person, and why did we ever start talking about them if we weren’t going to come back?” But I think that just comes from, what can I say—usual expectations. And I say, What can I do? That’s not exactly the form here.

DeWeese: Do you feel like over the course of your career your ideas about what a novel is or can be have changed at all?

Salter: Well, no. It should be interesting. That’s the main thing. And after that I suppose it has its own terms.

DeWeese: How do you think about structure as a screenwriter who—do you think about structure differently when you’re writing a novel?

Salter: Well, you should think about structure in a novel. Here I kind of played loose and easy with that, so you might say. I wasn’t concerned with it that much in this book—as I said, it began to evolve in a way. You say, “Well, I’ve either got to do this, and be more consistent with structure, and interweave these people back continually, or not.” So in the end I said not. At least not that much.

DeWeese: You also do something interesting with point of view. And it’s not unique to this novel. There’s a willingness to let consciousness float at times. Bowman’s obviously the main character, but there are important moments in which we move from his perceptions to other people’s perceptions. Do you do that intuitively, or do you have a sense of when you feel like it’s a good idea—

Salter: I don’t have a thing that clicks and says, “Here’s a good place for that.” It just comes out of the writing. I don’t know. I’ve done that—you might say I’ve gotten away with it—before. It’s been commented on before. But in one particular case somebody reviewed this book, but also me, in I think it was The Atlantic, or it might have been Harper’s—it was one of the two. It was back a ways, probably in April. I respected it. I mean, he knew what he was talking about. He complained about that, more or less.

“In fact, the deviation is what makes it read well, because it’s not expected, and it changed your mind in mid-flight, so to speak.”

DeWeese: Why complained?

Salter: Because you’re not supposed to do that. I don’t recall exactly—it wasn’t niggling. He was just commenting that this was an irregularity, and then he quoted a little place where it happened, it was three or four lines about sailing on a boat. It must have come from Burning the Days. And when I read it, I thought, Ah, that’s terrific. It just seemed rather wonderful to me. And I didn’t say that at the time [of writing it]—I mean, it was just written. So when you said is it instinct, it must be some sort of tendency, anyway.

DeWeese: It’s one of the things that I really admire about the book. There’s a certain power and maybe emotional involvement for the reader that’s derived from—it’s not omniscience, but it’s a willingness to move in that direction. And you said you “got away with it.” There’s somehow this understanding that one should never leave the head of one’s main character—

Salter: I don’t know, it’s one of these things apparently they teach. Like, the same point of view and, I don’t know, a lot of clichés about writing—generally with some solid foundation for teaching. But you know, I know that I can write that way, too, and if you know all the rules, you can—Joan Didion was asked how she approached matters of grammar, and she said, “Grammar is something I play by ear.” So if it reads correctly, then it really doesn’t matter if it deviates in some way. In fact, the deviation is what makes it read well, because it’s not expected, and it changed your mind in mid-flight, so to speak—the reader’s mind, of course.

DeWeese: It seems to me it’s a condition as a writer that you want, to feel that freedom to access the material at some other level that doesn’t have to do with rules.

Salter: Yeah, when you’re not going to get graded, you’re free to do anything you like. Of course, that can result in some horrific things, too.

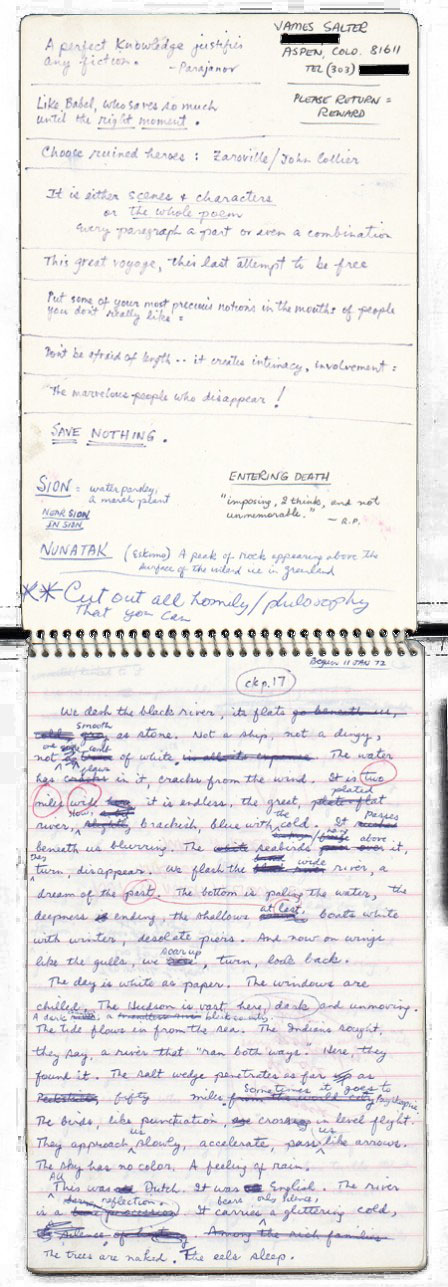

DeWeese: And you write in notebooks, longhand. As someone who has written or been around computers from the time I was young, I often worry there is a kind of material that is accessed through using notebooks, writing longhand, that we can’t access if we’re sitting in front of a computer. Do you feel like that process of writing in a notebook offers you an opportunity to discover material that you wouldn’t find otherwise?

Salter: Well, I write e-mails on the computer, of course. And some e-mails can be long, and you’re editing them as you write, or at least I am, deleting sentences and going back, but it’s not quite the same process for me. But I don’t know if we’re seeing the same thing, since you grew up one way, and I another. I’m sure you can write longhand, too, but don’t you see it may be different in a different way for you? I don’t know. All I can say is I feel a great informality in writing longhand. I feel I’m alone in the house, I’m just wearing a bathrobe, I don’t have any shoes on, nobody’s going to bother me—I have that feeling when I’m writing longhand. I haven’t sat down to compose, so to speak. Also, you can write anywhere, you can go out and sit on a—I guess you can do that with a computer, too—but all you need is a scrap of paper, an envelope. And you can attack a paragraph, or jot down a lot of ideas that might let you into something—I mean something you want to do, the thing you’re trying to do. It just seems to have an ease for me that I appreciate. I’m certainly not recommending it. I think you should do what feels right to you. It’s often been commented that writing is different now, because you can write so fast, so freely, and it gets more word clogged. I don’t know if that’s true. That wouldn’t happen to me in any event, but maybe that’s true generally.

DeWeese: Why wouldn’t it happen to you?

Salter: I like to cut out words rather than add more words, more description.

DeWeese: I want to ask about a line in All That Is. It’s in the scene where Bowman is telling his mother that he’s going to marry Vivian: “It was love, the furnace into which everything is dropped.” The line is written in such a way where I think we’re meant to understand that it’s her observation.

Salter: Well, it’s certainly not his. We know that. And it’s certainly not Vivian’s. It’s his mother, or the narrator, or the author. And I didn’t particularly puzzle over it. I just wrote it.

DeWeese: Many of your characters are undone to varying degrees by love relationships, so I’m wondering if you feel that observation is correct, that there is something destructive about love relationships. Is there a danger to love relationships that you feel your characters are encountering again and again?

Salter: I don’t think this is a personal feeling, I think everybody knows this, don’t they? All literature, all personal experience—I wouldn’t say the word is “danger,” but the complexity of it…and I wouldn’t say “fragility,” exactly—but the variableness of it, and how close what you feel and what you know conforms to what everybody tells you you should feel or you should know, yeah—I think that makes it a central issue in people’s lives.

DeWeese: One of the things that appeals to me about so much of your work is that there seems to be an exploration of this tension between enchantment and disenchantment. I’m thinking about the end of The Hunters, where we have a sense that Cleve is trying to remain connected to the beauty of what he’s doing, but is becoming more and more disenchanted with the realities of it. It seems to show up in your work again and again, but I don’t know if you think about it in terms of enchantment or disenchantment.

Salter: I don’t think I do.

DeWeese: How would you describe that tension that your characters seem to be trapped in?

Salter: Well, let’s jump to another book, or two, or whatever. Here’s Light Years, there’s not really enchantment in here.

[At this moment, DeWeese spilled coffee on his notebook and the Salters’ couch, destroying the continuity of the conversation. The Salters’ reassured him that this was unimportant, even going so far as to claim they were thinking of having the furniture cleaned anyway. Doubtful. Kind of them to say so.]

Salter: I don’t think there’s enchantment or disenchantment, either one in [Light Years]. It’s the story, really, of the impermanence of a really privileged and perhaps deceptive marriage—I mean deceptive to the reader. And the book even says that—there’s what you see, and there’s life behind that, the real life. So I don’t think that they’re disenchanted. She probably, mainly, is an impulsive person, a dramatic person, and self-destructive to an extent, strong-willed, and decides she’d like to turn that page in life. I don’t know if that corresponds to this great wave of women finding themselves, dating back to the early 60s, 70s, when all this was renewed with Betty Friedan’s book, and then the consciousness-raising, that whole feminist history. That wasn’t in my mind—it doesn’t really have anything to do with that. It was just a natural feeling I think anybody could have at any time: “I’d like to be living another life” or “I should be living in a different way.” And it just happens in this marriage. So something that was really very appealing begins to fade, and what happens to them afterwards, that’s really the book. But that’s what I think the book is. What the reader thinks the book is may be not exactly that. I mean, that’s always the case—you don’t know what you’ve written until people start telling you what you’ve written.

DeWeese: Religion rarely comes up directly in your novels, but I do often sense that there’s a kind of spiritual component, or characters striving for a connection to something. Do you think of that striving as a search for spiritual connection, or is it wrong to call it spiritual?

Salter: I would say it’s closer to a moral striving than spiritual, though I don’t know how close those two words are, really. “Spiritual” suggests something a little different. I think in The Hunters there’s a moral element. And I suppose—I mean, you reveal yourself through writing, right? Even though you’re writing about other people and other things, you have a mask you’re behind, you’re not obliged to the autobiographical elements, you can alter or conceal to an extent where they’re almost indiscernible—but you are writing what you are, all the time. There’s really no way of getting away from that. So the element you’re talking about, be it spiritual or moral, I suppose is there. It’s not put in the forefront. I would say it must be implicit somehow in details, and the observations of things, and the occasional conclusions that the book or the section of the book makes. Also in things that people say.

DeWeese: There’s also a strong sense of an aesthetic—a kind of existential aesthetic. Maybe this is what you mean by “moral”—there are better ways to live, or better ways to behave. But in All That Is, with Bowman, it’s sometimes difficult to tell to what degree Bowman is driven by aesthetics, and to what degree he occasionally floats along, kind of going with a flow, versus at other times pursuing some kind of desire to introduce into the world objects of aesthetic beauty—in his case, literature.

Salter: I think that’s right, and that unevenness is part of the book. It corresponds, in a way, to people coming and going, to that feeling—that almost river-like or tidal sensation. I think when you finish reading it, if you liked it, you have a feeling of a whole era having passed, and yet what exactly passed? It doesn’t have a lot of solid benchmarks. The president gets shot—that’s almost as far as he goes. So I think that’s right—he varies. He is varying. Some things are more important or come to the surface at times, at times no, he’s carried away. He’s carried away by love, or what he takes for love—or what I take for love. And sometimes not.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

James Salter’s novels include A Sport and a Pastime, Light Years, and Solo Faces. His story collection, Last Night, was published in 2005. A collection of his non-fiction, There and Then: The Travel Writing of James Salter, also appeared in 2005.

Dan DeWeese is the author of the novels Gielgud and You Don’t Love This Man, and a story collection, Disorder.