Craft Q&A

Jenny Forrester, author of the memoir Narrow River, Wide Sky (Hawthorne Books), has a musical gift in her language, and I inhaled her book as I would an instantly loved album. Yet it is a piercing story. In the shadow of the Colorado wilderness, Forrester relates traumas that build and shape her until she leaves the gorgeous region. Forrester grew up primarily in Mancos, a small, conservative Colorado town, with a younger brother and their single mother, a teacher who struggled financially. Today, Forrester is a politically engaged feminist. She curates the long-running Unchaste Readers Series in Portland, Oregon, and has published anthologies based on the series. —Alex Behr

Alex Behr: In the chapter “Sex Education,” you use precise imagery like a photo, but with a sly twist: “powder-blue-western-style jacket with white piping, scorpion bolo tie, and shiny cowboy boots ... I knew how much he loved math, but he was Mormon.” The scorpion tie seems to foreshadow your relationships with boys and men in this book. How difficult was it for you to write about the abusive interactions, since in writing, the same parts of your brain are triggered as when you first experienced them?

Jenny Forrester: It took a long time to write the book—all those vignettes and layers and editing, setting some memory down, coming back to it. Sometimes, I was traumatized. Sometimes, I thought something was funny, but when I read it aloud to my family, they didn’t see it—in fact, they felt the opposite. It was traumatic for them, too, to hear the stories. Sometimes, I read something to an audience that laughed at something really sad and hard. I learned how to manage all that, too. It all helped me take a bird’s-eye view of emotional landscape as an idea, and my landscape, in particular. I’d say it took everything out of me emotionally and spiritually and put me back together, too—art and I creating each other.

Behr: Sometimes, as a reader, I wanted to take your family and move somewhere where your mom could have a better job and not struggle so much. There’s no “nobility” in poverty. It’s a cultural, geographical, and sociopolitical construct that is so painful to read about through your perspective as an artist/writer and sensitive girl. How does your understanding of that type of poverty (marked by geography) affect your understanding of the conservatism and racism sometimes found there (which is, of course, embedded through all levels of society)?

Forrester: It’s another one of those victim-blaming agendas—setting up a lie that poverty is always a choice, and on the other hand, it feeds shame over having enough to live beyond mere survival, so that only the super wealthy are outside the hold of the nobility-in-poverty idea. Meanwhile, there is absolutely an agenda that white supremacy created and re-creates with regard to money and value and et cetera—there’s a relentless kind of subnarrative that less-wealthy whites are supposed to buy into.

My mom used to say, “Life is all about money,” when she wasn’t saying, “Life is all about sex.” I really think she was onto something more than the obvious need for money in order to survive capitalism. I also think there’s a great deal to parse from the use of the word nobility. I remember singing the song “The Old Rugged Cross,” about suffering in life and exchanging it all for death and a crown. I’m interested in continuing to write more about the intersection of religion and money and religion and white supremacy in the next book in a subtle way, of course, using landscape and memory.

Behr: When writing about the past, a writer creates new memories about it—how memory works is that you re-create memories each time. What would you have added to the book now that you’ve talked about it so much? How did you create a persona that allowed you to “forgive” yourself—and your mom—despite faults and mistakes?

Forrester: I didn’t forgive myself—I don’t know that I need to buy into the cult of forgiveness in order to learn and move forward. I’m sort of anti-forgiveness in a way. I want to write more about that in the next book. But having said that, I forgive my mom. She did the best she could. There’s a line in the movie How to Make An American Quilt: “Of course, I forgave him. That’s what you do when someone dies.” I don’t blame her for the things others did to me. I place their actions at their doorsteps. I wish she could’ve listened to me at the time, but she couldn’t. I wrote her forgiveness of me, though, because what others did to me was more bearable than what I’ve done to others. I wrote that I no longer believe in redemption, which is the next level after forgiveness, maybe. I don’t believe any of us know exactly how memory works, either. I think memory is tricky. I think it’s complex and specific to individuals. I think what I did was create a container to handle my memories, which is different than changing my actual memories. Some scientists might disagree, which is fine. I’m not a scientist. I’m an artist so I wrestle with metaphors and my personal truth. Patriarchy doesn’t want us to trust our own minds or our memories—I think we need to remember that.

I love the writing craft concept that there’s The Person, The Writer, The Narrator, and The Author. My Person lived it, My Writer gathered the memories and words, My Narrator spoke it/wrote it, and The Author determined who would come forward at various points because they were the best one for the particular task at hand and for how the narrative arc would work.

Behr: How do terms relating to body images affect you, since you write so movingly about weight, eating, etc.? How did you protect your daughter in a society that is so fat-phobic?

Forrester: I don’t know if I can protect my daughter from a fat-phobic and body-critical society. In fact, I know I can’t. It’s too powerful. I’m just one woman, one mother. I’m for the word fat—it’s what I am.

Behr: How did writing about how your mom controlled and commented on your eating (a basic need) change your memories of her?

Forrester: I don’t think anyone with a normal body weight, regardless of eating disorder history, can explain anything to me about being fat or suffering fat phobia, which is what was so hard about being raised by a normal-weight woman. Like all normal/socially accepted-weight women, she didn’t have any understanding of what it was like to inhabit the kind of body I inhabit, but she loved me more than she loved herself, and being a woman with a strong moral conscience with a strange sense of conformity, despite being such a nonconformist (which makes her such a great literary character, too), she couldn’t have imagined changing the world for me or addressing the assholery of the world. So, she focused on me, wanting to change me instead—wanting me to fit in to societal norms. There was always that tension. It makes for good writing material and makes me stronger as an advocate of bodies that don’t fit. I’ll be forever growing that strength.

Behr: Roxane Gay writes in Hunger: “This is the reality of living in my body: I am trapped in a cage. The frustrating thing about cages is that you’re trapped but you can see exactly what you want. You can reach out from the cage, but only so far.” How hard was it to write about your body, since as women we are socialized to make it public? It’s always a public thing/declaration/choice.

Forrester: I guess I’d respond with the opposite state of being. Men are allowed to be big, even fat. They get to have bodies that do things, that go places, that expand and contract. They get more and better medicine and jobs and money in order to do those things—everything supports them on all levels while women are forever seeking reproductive autonomy. A cage indeed. Roxane Gay has said that if she were a CIS white heterosexual man, she’d be president. I completely agree.

“Scientists do much to refute memory, but I think the more brain-changing and life-altering, and therefore the more literary influence, is landscape.”

Behr: I cried when I read the scene of your mom drowning. Why did you decide to put how she died late in the book? I feel like it’s also an echo of the title: the air she needed underwater, on a pleasure trip, was denied to her.

Forrester: Originally, the book was in this very circular essay-type format (hard to follow/didn’t have the emotional effect I wanted), then it was exactly linear (which rendered it boring), then the braided idea came out. Cheryl Strayed had her mother’s death in the beginning, and I thought that was effective (I bawled), but I knew that writing that Mom died in a cave diving accident could make people think she was a wealthy lady on vacation, an unfair assessment of her life and being. So, I had to show her wholeness and more of her life before we got to that point. It sucks, but it’s true—many readers wouldn’t have cared as much about her had they not known her more fully. I had to make sure people loved her as she deserved to be, as we all oughta be—ultimately my goal as an artist is to show love.

Behr: Did you go through the first sentences of chapters to see how they connected, like thread? Chapter 6 begins with a teacher handing out hunter safety handbooks, and chapter 7, with your brother shooting a deer. Chapter 8 begins with you standing, with your finger near the trigger of a gun, and, later, you begin a chapter about women victims of domestic violence. It’s subtle but devastating.

Forrester: It took a long time and was the hardest thing to put together, so thank you. I’m an intense person, too. Intense sensitivity probably leads to that.

Forrester reading to a packed house at Broadway Books in Portland, Oregon.

Forrester reading to a packed house at Broadway Books in Portland, Oregon.

Behr: How did you decide to re-create dialogue in scenes? (I’m the daughter of a reporter, so perhaps I feel uneasy putting words in people’s mouths, though I know it helps create scenes and deepen characterization.) How did you hear their voice or figure out when the voice was “right,” especially your mom?

Forrester: We don’t speak the best way to show in dialogue—as an artist, I took liberties with it. There’s a tone to a conversation, there are the words spoken, there’s what sounds right on the page. Coming to this as an artist, rather than as a journalist, I think the betrayal would be if I didn’t get what they said right, if that makes sense. Betrayal would be if I don’t make them sound right on the page. If I put down their vocal pauses and their slips that made them sound foolish as human beings, that would be a betrayal. It’s more about the spirit and character of a person’s speech that interests me than the exact words spoken. If anything, I want to make them sound better—that is, in command of their speech and their thoughts. I’m their speechwriter.

Behr: You write about reading your mother’s journal entries after her death: “She wrote about my being overweight again as a nightmare she’d had. I cried rage at her.” You learned about the violence she endured: “pain at the hands of men on dark roads.” You write with economy and beauty about devastating events. How did you find that language? And is it a language your mom would intuitively understand?

Forrester: My mom loved language—she worked on her Spanish throughout her life, never satisfied, and she worked on her English, too, and again was never satisfied. She was always learning. She didn’t like the way I spoke, often correcting things I couldn’t and wouldn’t correct, the two of us being from different places, different ages and times. In Mancos, she was looked down on for being so educated. That tension taught me about language, too. And again, I’m always going to go back to landscape—there are things we learn to speak to and about depending on geography and topology and space.

“I’d say the book took two decades to write because it took two decades to become the writer and person I needed to become.”

Behr: How did you finally decide you were comfortable with your voice—in its jump-cuts, use of reconstructed dialogue, in its connection to land/people/regrets?

Forrester: Ariel Gore, who I’ve studied with, could’ve told me not to write a million things in a million different ways—my descriptions, my experiences were not urban, educated, progressive descriptions or experiences. She never shut me down. She was utterly patient. She let me grow and learn and keep writing. I’d say the book took two decades to write because it took two decades to become the writer and person I needed to become.

Behr: Anti-domestic violence was one of your earliest causes, so how have the ramifications of that issue changed for you now, when women more than ever are trolled and demonized for being feminists? You also have compassion for women who may come from the types of communities you deliberately left.

Forrester: I have a keen awareness of the vastness of patriarchy. I know Mary Daly did some wrong things, but when she wrote about the Background vs. the Foreground, it explained so well what I was seeing—an overlay of patriarchy over the natural world, like pavement over rivers, houses over mountainsides. The more I learn about gender and sexuality and the more society as a whole transforms, the stronger I feel that we have to have compassion for each other and the more anti-violence I become. I’ll be forever softening to the ways women and the gender non-binary among us have to navigate the violence of men and their patriarchy. I’ll be forever strengthening my mind and heart to stand against that violence and its effects on us all.

Behr: During your book tour, how did it feel to be back in Colorado? Do you feel Portland is in a bubble?

Forrester: I loved being back in Colorado—the words from the book just came out of the landscape. It was a powerful thing to have the land speaking as if we’d written the book together—the landscape and I. Hard to explain. I hope the reader understands. Portland is totally a bubble, and it’s a bubble in a bubble because it’s got a very liberal reputation but it’s such a white city—it’s not as white, percentage-wise, as some of the tiniest towns, of course. I love Portland, though. There are some good things happening and great people here. I’m so grateful to have become a writer here—I’ve been able to learn things I don’t think I would’ve learned in Colorado or in Arizona where there are also lots of white people, but progressive ideas are held only in pockets of the more urban areas.

Behr: In writing groups, how do you protect your work from harm, especially since you’re writing about the harm you experienced?

Forrester: I work hard to keep my own counsel, meaning I’m open to feedback, but I have to be aware of what doesn’t apply. Separating my feelings from my art helps. I don’t trust anyone who says we learn more from criticism of our weaknesses than from praise of our strengths. If I were to go back to the things I understood as a child, god has more to give than the devil, and of course, I’m not religious anymore, but it’s a great metaphor. Also, I’m for spaces that are specific to particular populations. White men had white men’s clubs for so long and from the beginning for a reason—these exclusive spaces hold huge amounts of power.

Behr: You said at a reading here at Broadway Books: “I saw two moose, starving, eating fresh pussywillows. Moose do it all. They do everything.” How do you bring nature into your life now? Or is it always present?

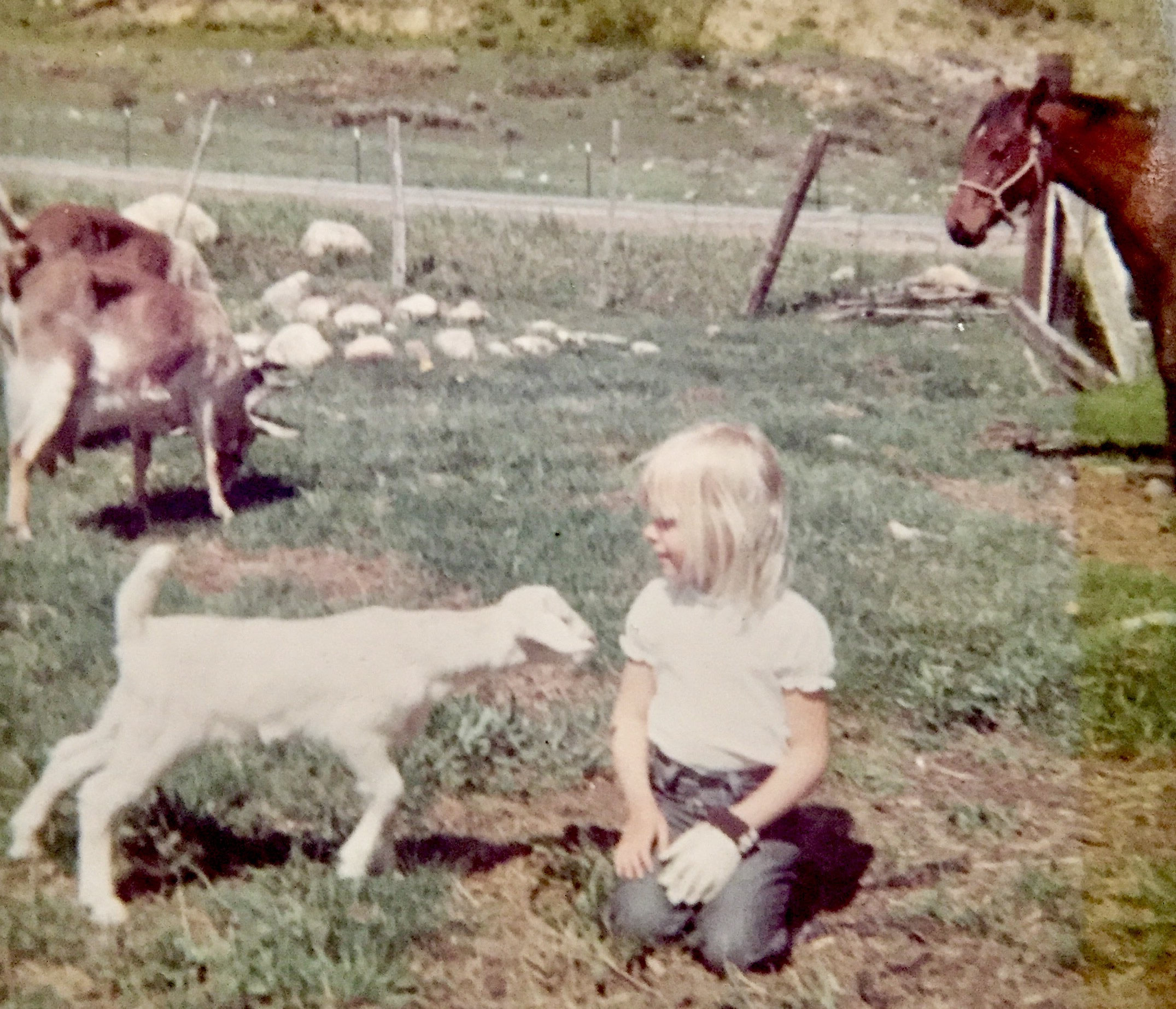

Forrester: Ever-present. Everywhere I go, I am walking in it, which is why big, paved, smoggy cities are so hard for me, despite loving people as much as I do. I spent three days in NYC with my family and by the third day, I was done. Scientists do much to refute memory, but I think the more brain-changing and life-altering, and therefore the more literary influence, is landscape. We attune ourselves and are attuned to it for the rest of our lives. I’m so grateful to have been a small child in the mountains with an abundance of wild and domesticated animals, including farm animals and trees and wild streams and untethered winds, where the world wasn’t covered over by houses and roads. I’m walking in the world, seeing what was there before—the ghosts of trees and rivers and bears. I wish we all were—imagine the possibilities.

Behr: Throughout your book, you write about the threat of becoming Mormon. How did that eventually influence forming Unchaste?

Forrester: I want to be free. I want women to be completely free. I know men won’t grant this freedom, so we have to take it. We have to manifest it from within and push it forth constantly and with great force. Laws are created for and against patriarchy—on that level, the path to freedom continues. Patriarchy would have women as servants, as vessels, et cetera, only to abandon us when our usefulness to them has passed—they better themselves at our great expense at every level and in every sphere. They make exceptions for their daughters to seek freedom when it makes them look better, but it’s a superficial exception. I feel the threat of patriarchy as ever-present. Even now, The Handmaid’s Tale is popular. When I read that book, I thought it was about Mormons and white supremacy. So, I know this threat is real. And it’s not just Seventh Day Adventists, but Joseph Smith had a particular need to bind women to his sexual will, to bolster his fragile ego, to protect his fragile soul. He was a fast learner and took what he could from each woman and moved on to the next, hiding it all under the guise of marriage, the definition of which patriarchy is constantly struggling to maintain the power to define.

Behr: Since you started Unchaste, more than 250 women and nongender-conforming readers have shared their work. It’s a remarkable thing to create that space for writers at all levels and styles to read aloud.

Forrester: Unchaste has been a joy and has changed me and allowed me to grow as much as anyone else. I’m grateful. The work I do is in exchange for the life I get to live because of The Unchaste.

Behr: What was your experience in writing about abusive people—girls, boys, young men, family members—in terms of catharsis, or not?

Forrester: When I finished the last draft of my book before beginning the query process, I turned the last page, marked my last edit and sunk to my knees crying. Relieved at last. Maybe not relieved of all things, maybe not forever, but then and for those things I wrote, I was granted some peace.

Behr: What section was easiest to write? Hardest?

Forrester: Easiest to write: my mother’s cooking. Hardest to write: my mother’s dying.

Behr: What has been your experience responding to the public through “finishing” the manuscript (is it ever finished?)? Were there any cautionary tales you wanted to avoid while writing this? Or did you decide to be brave and fuck it if you pissed off people?

Forrester: I do feel the work is done—it creates questions in the reader’s mind, it makes people think about their own lives and thoughts. It doesn’t have a pinpoint end. That’s what I wanted—something round. I didn’t want to write cautionary tales like “Don’t do drugs” or “Don’t have sex with lots of boys” or “Honor Thy Father and Mother” or any of that—I wanted to un-write those. I wanted to show my understanding of feminism through my life’s lens.

Behr: How have the writer Lidia Yuknavitch (Chronology of Water, The Book of Joan), and Rhonda Hughes, your publisher and editor, influenced you?

Forrester: The thing Lidia did was be an example of throwing caution to the wind—I have a very taut idea of what scene-driven literary memoir oughtta contain. Lidia doesn’t. She gave me room to complete what I needed to complete. Rhonda helped me by telling me how much details matter because readers are emotionally invested in us—there were things I didn’t think readers would want or need to know. She said they wanted to know and needed to be shown. She believed in the story. She understood it. There’s nothing as valuable as a close reader. I’m so grateful to know the both of them. Beyond the beyond grateful.

Jenny Forrester has been published in a number of print and online publications, including Seattle’s City Arts Magazine, Nailed Magazine, Hip Mama, The Literary Kitchen, Indiana Review, and Columbia Journal. Her work is included in the Listen to Your Mother anthology published by Putnam. She curates the Unchaste Readers Series in Portland, Oregon.

Alex Behr is the author of the story collection Planet Grim (7.13 Books). Her last interview for Propeller was with author Lance Olsen.