Reading Lines

This is not an age of beauty...

My heart believes it is a muscle

of love, so how do I tell it it is a muscle of blood?

—Emilia Phillips

I WISH IT WERE an age of beauty. Just because there’s plenty of it around doesn’t mean we appreciate or understand it. I feel ashamed of how much beauty matters to me, how much time I spend admiring my husband’s thick hair and strong back. I know I am supposed to love him for his character, and I do, of course, but I also love him for the elegance of his hands and his sharp jaw. Beauty is not democracy. It is a tyranny, and a master I constantly struggle not to resent, because I love fine perfume and paintings of fat naked women and silver art deco mirrors and elegant language and the silk scarf on that girl on the train this morning, its blue brightening her yellow hair. I don’t know how to make peace with beauty. Our current culture’s major lines of rhetoric are, at best, moralizing lies, and at worst, insane.

ONE: Beauty is Objective: The draconian model of beauty as either rare and expensive or exhausting and time consuming. A walk outside refutes this. Smiling two year olds, fat purple pigeons, flowers, sunsets everywhere, all common as dirt.

TWO: Beauty is Subjective: The patronizing fairy tale that we are all equally beautiful “in our own way.” Or “on the inside.” This is cold comfort to anyone who has ever felt the sting of romantic rejection, or watched an even-featured moron steal every scrap of attention in a room.

THREE: Beauty is Irrelevant: Come the revolution, such lookist preoccupations will dissolve into an egalitarian ether. For better or worse, as long as there’s desire, people will still be preoccupied. They will just pretend harder that they love you for your mind.

FOUR: Beauty is a Mating Strategy: In order to secure resources for your offspring you must fool mates into seeing your assets as more symmetrical and youthful than the competition’s assets, and you must do it now, for the sands of time run quickly and the world mints new twenty-two year olds every day. Maybe, but I like to look at pretty girls, too. Though they provide me no reproductive opportunities, they still decorate the world.

“If it truly were an age of beauty, we would have better theories. Or at least more respect for the terrible power of it.”

FIVE: Beauty is Evil: Take off that lipstick, you look like a whore. If I had a dime for every time I heard some Gen X-er decry Instagram girls, selfies, or the endless cash women spend on shallow garbage like Tom Ford Eye liner, I could take a year off, get some rest and a chin lift. Maybe then I wouldn’t feel quite so judgmental about young girls using new technology to do the same old things.

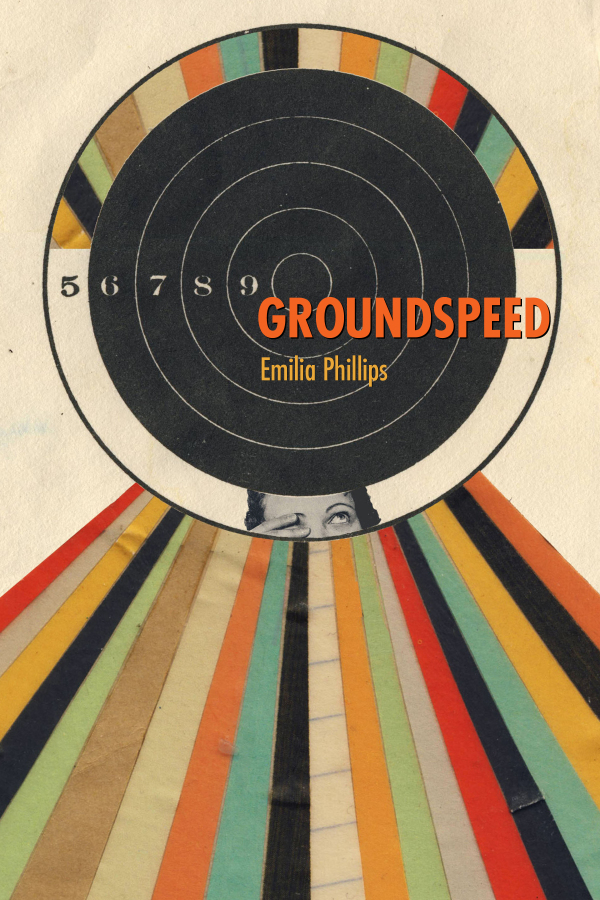

Poet and essayist Emilia Phillips, author of Groundspeed (2016) and Signaletics (2013).

Poet and essayist Emilia Phillips, author of Groundspeed (2016) and Signaletics (2013).

IF IT TRULY WERE an age of beauty, we would have better theories. Or at least more respect for the terrible power of it, how it demands our attention and shapes our experience from the moment we open our eyes.

I always ask my female friends if their mother was beautiful, because it tells you so much about how they see themselves. I had a beautiful mother who hated her looks, though thankfully she kept that second part quiet most of the time. I prayed to be beautiful like her. I was not. I hoped I might overcome the shallow longing for it, be interesting looking instead. I hoped the rewards of noble transcendence might outweigh the rewards of adoration and glances and love and the pleasure of seeing my own face in the mirror. It did not. I eventually grew more beautiful, of course, as young girls do, but I couldn't see any of it, and it did me no good.

And still, the barometer of my self-loathing day to day, whatever its cause, a fight with a friend, a failure at work, is directly perceivable to me in the mirror. On my best days, I look fine, lovely even. The worst, I’m repulsive—a lumpen, quivering mass of chins. Knowing both are hallucinations made of brain chemicals and social comparison hardly helps, though sometimes the effect is so sudden it makes me laugh out loud. The first three months after I quit smoking, I was monstrous, every single day. I had not heard tell of this side effect, but it nearly broke me, lung cancer be damned. Thankfully, a casual female acquaintance who quit the year before mentioned that it happened to her, too, and that it did go away eventually. Bless her.

I think this wrestling with beauty is especially difficult for people who concern themselves with aesthetics. I carry a medium sized burlap bindle of commonplace anxiety about my looks, but a train car of existential anxiety about my tastes. I make irrationally powerful and immediate decisions about what I like and what I don’t like to look at. This has more far reaching effects than you might think, and I find it an ugly feature of my character. I’d rather not be the sort of person capable of looking at a work of art or a human being and thinking Ugh. But I am that sort of person. It’s awfully hard to convince yourself that beauty doesn’t equal love when you know in your own dark heart that you love what it beautiful, and you can’t help it.

Wendy Bourgeois is a poet and writer. In the fall 2017 issue she wrote about sex, death, and lines from Philip Larkin.