Craft

Tatiana Ryckman is the author of the flash fiction chapbook Twenty-Something and the flash nonfiction chapbook VHS and Why It’s Hard to Live. Her newest publication is the novella I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do) (Future Tense Books), a series of missives, observations, and confessions from a narrator involved in a long-distance relationship. Ryckman chatted with us about the book’s genesis and development, and also provided a handy chart that serves as an infallible guide to intimacy.

Propeller: In the acknowledgments section of I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), you say you are grateful for “Jordan Shiveley’s drawing of two mice fucking, which inspired this obsessive manuscript.” Your book is about emotional terrain that is trickier and more complex than the drawing, though. When did you know you wanted to write about a romantic relationship, and what were some of your other inspirations?

Tatiana Ryckman: I love that drawing! Something about it, the first time I saw it, made me so incredibly sad. But now when I look at it, it’s not how I remembered. But that’s also the premise of the book—we have this strong emotional response to something, or someone, and instantly they (as their actual self) disappear, and all that’s left is the fantasy we build in their place. I suppose that feeling is a sort of inspiration for the book, though it doesn’t just happen with romantic partners. I feel like I’m constantly updating my assumptions about people. I enjoy being surprised. There are also a number of quotes in the book, and I would say they were a big source of inspiration. They are the ideas that excited me the way a new person might. Maybe the book was just my way of showing strangers my favorite things. The form itself—that of written missives from a lover to their beloved—came pretty naturally. Now that I’m not working on the book I find myself actively looking for someone to send my thoughts to, as if they aren’t for me. Perhaps being a writer is just that impulse: the idea that a thought needs an audience to exist.

As for deciding to write about romance... I’m not sure there was a moment when it occurred to me. My mother has long accused me of only writing about sex, so I guess this book has been a long time in the making.

Propeller: I’m sure you reminded your mother that our preoccupations are the result of both nature and nurture, so the credit for only writing about sex must go, in part, to her. But I want to ask about one of the quotes—the one from First Corinthians: “He who unites himself with the Lord is one with Him in the spirit.” Your narrator says this is “a reminder that we are what we worship.” How do you feel about modern warnings about not “losing yourself” in a romantic relationship? Are there options?

Ryckman: Ha! I’ve reminded my mother of all kinds of things, but I think I’ve forgotten to mention that.

Is that a particularly modern warning? Perhaps. Maybe people used to see having no self as devotion. As for options, I think there are a horrifying array of options. Variety is the spice of life, but I personally find the paradox of choice to be crushing. I think this is why a strong self is important. If nothing else, how can I be devoted to someone if there is no I to devote?

“I realized almost all of my interactions were based on certain assumptions about the way people are, what they’ll say, the imaginary conversations I have all day long in my head.”

Propeller: It’s a good question. And you’ve done something else interesting with the I in the book, which is to leave the gender of the narrator—and of the beloved—unmentioned. Why did you decide to write the piece that way?

Ryckman: I’m so glad you noticed! It seems almost every review of the book has assumed the genders and it’s a little frustrating. There are a few reasons why I avoided gendering the characters. The first is that it didn’t really make sense to me to do so. When you write to someone you’re familiar with, you don’t point a lot of arrows to things like their genitals (though, there are plenty of mentions of genitals in the book, just not the characters’). To make a point of describing a character seemed like the narrator/lover would be writing for some imaginary audience (my readers), not for the beloved (the narrator’s reader). So, logistically, it seemed fitting. But I also liked the possibility that readers might identify with the narrative and feel that these were missives they had written (or at least thought) at one point to their own beloved. It would become their story. And I didn’t want that experience to be limited by a superficial limiting factor like gender. And I really do think it’s superficial. The fact that everyone assumes the genders seems like evidence that it doesn’t really matter whether they’re there or not.

Propeller: And the missives we read in the book are compact—the book is composed of many vignettes. What was the composition process like? How much were you playing with the order of vignettes, and what did you learn about writing by crafting a book from a large number of discrete pieces?

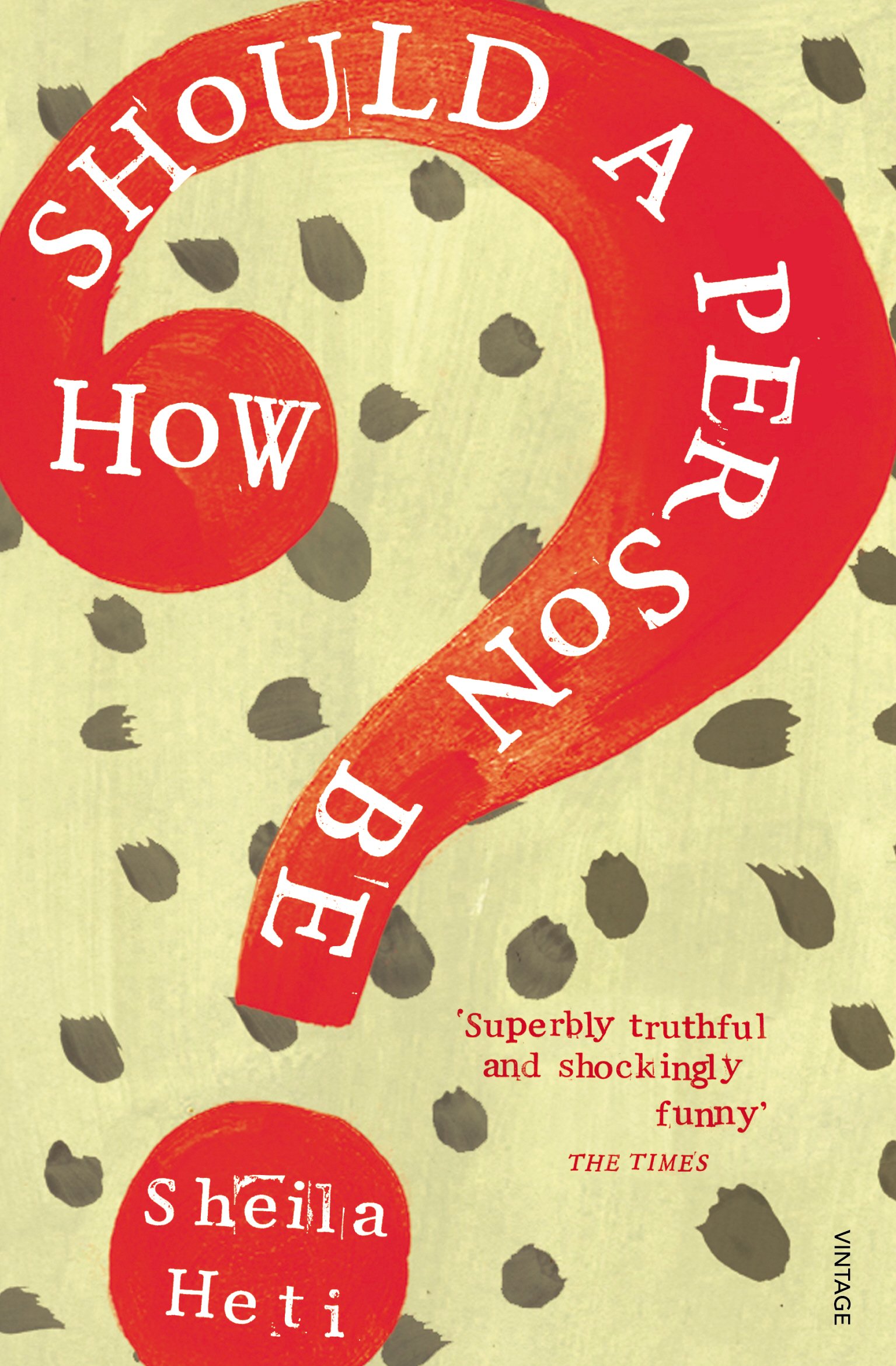

Ryckman: I’d only ever written flash (fiction and nonfiction) leading up to this book, so I’m not sure I learned anything particularly new about crafting discrete pieces. Possibly about linking them? I remember reading a essay by Sheila Heti, where she talks about not being able to remember everything in How Should A Person Be while she was working on it, and forgetting where things happened. This book is by far the longest thing I’ve written (educational books aside), and for me it was a great exercise in devising scenes and linking them in a meaningful order. Sections were shuffled, deleted, and rewritten. Sometimes when preparing for a reading I’m still surprised by the placement of a scene. I think I learned something about developing plot. Maybe developing is too self-congratulatory a word. Perhaps... “having any sort of plot at all” is more accurate?

The composition was pretty scattered at first, but I didn’t know I was writing a book. The first part I wrote was section one—after seeing that drawing of Jordan’s. Those first ten vignettes came out all in one sitting and I thought that was that. I wasn’t sure if it was a prose poem or a flash fiction piece. I was reading at Owen Egerton’s One Page Salon later that week, which is specifically for reading a single page of a work in progress, so I thought it was a good opportunity to try it out out loud and see how it felt. After the reading Owen asked me how far along I was in the manuscript, and I remember being a little horrified. “Oh, no,” I said, “That’s all there is.” But the idea didn’t go away. When I realized almost all of my interactions were based on certain assumptions about the way people are, what they’ll say, the imaginary conversations I have all day long in my head—I realized there was a lot more to unpack with that first piece.

Some of the other sections came together in a similarly cohesive set of ten, or were deliberately written that way, and other sections just came from notes and observations that were collected and organized and shaped.

Propeller: The book tracks two different kinds of distance: the physical distance between the characters (they live in different cities) and the emotional distance between them. There are points at which they wonder about the relationship between their physical separation and their emotional attachment, and though they have some theories, I’m wondering what you, as the author, feel about the relationship between physical separation and emotional intimacy?

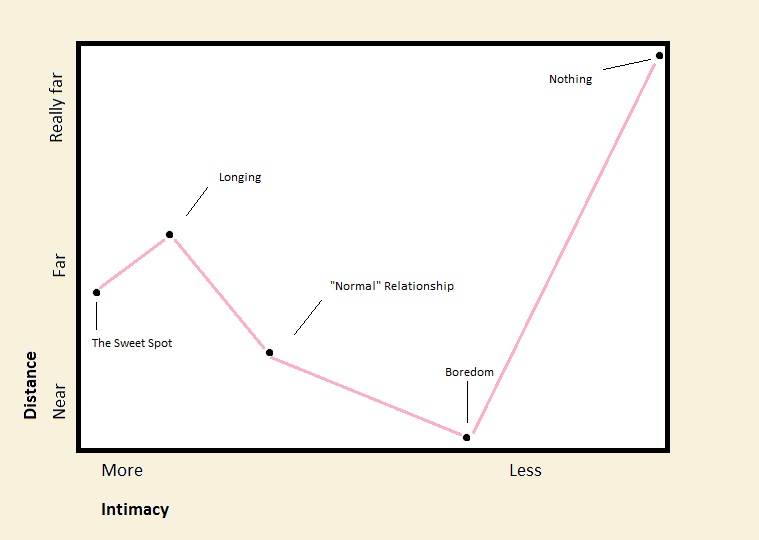

Ryckman: Thank you so much for noticing that! It’s a really nice observation. I think the relationship between distance and intimacy is something like this:

Propeller: I can’t help but notice that you’ve put “‘Normal’ Relationship” in a position that isn’t the highest intimacy, and “The Sweet Spot” near the spatial category of “Far.” What dynamics do you feel make separation more intimate? Or conversely, what makes a “normal relationship” less intimate?

Ryckman: That may be my latent (or maybe not so latent) skepticism, or a weak attempt at a joke (or some combination of the two). And yet. The thing that I think gets lost in proximity and familiarity is actually seeing a person. In My Dinner With Andre, Andre Gregory describes looking at a photo of his wife as a young woman, how he’d always seen it as a sexy photo, but one day after many years he looked at it and realized that the woman in the photo was incredibly sad. It wasn’t a sexy photo at all! There is this illusion that is so easy to settle into, which is that if we see someone every day, they aren’t changing, or we forget to be sensitive to those incremental shifts. I think distance can help maintain that sensitivity. At least for a time. But I’m not sure my ability to graphically represent data is up to a third dimension.

Tatiana Ryckman was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and now lives in Texas. She is the author of two chapbooks of prose, Twenty-Something, and VHS and Why it’s Hard to Live. She is Assistant Editor at sunnyoutside press and her work has been published with Tin House, Entropy, The Collapsar, fields, The Establishment, Opossum, Diagram, Barely South Review, and others.