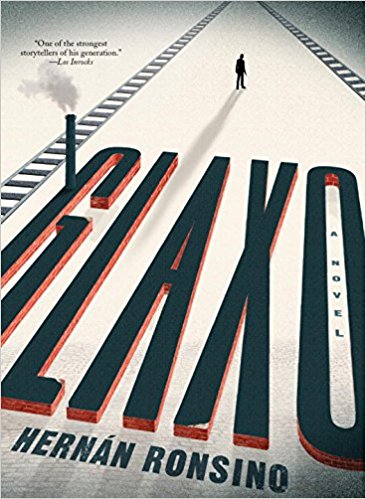

Aisles

Glaxo

by Hernán Ronsino

Translated by Samuel Rutter

Melville House

here’s a new road, a link road, which looks more like a closed wound,” says Vardemann, scanning the cleared cane fields of Argentina’s pampas. “It’s a road that looks like the memory of a wound in the earth that won’t heal.”

here’s a new road, a link road, which looks more like a closed wound,” says Vardemann, scanning the cleared cane fields of Argentina’s pampas. “It’s a road that looks like the memory of a wound in the earth that won’t heal.”

There are wounds betrayed in Hernán Ronsino’s Glaxo, injuries divulged even as the characters wish to conceal them. Ronsino writes of four friends—Vardemann, Bicho Souza, Miguelito Barrios, and Ramón Folcada—who once shared a love of breaking horses and American Western films. Disloyalty, though, has confused the virtue of the John Waynes and the Kirk Douglasses. At some point the mock gunfights acquired live ammunition, the crimes and vengeances were no longer pretend, and each character’s testimony, whether defined by avoidance, nostalgia, denial, or even reenactment, generates a twenty-year recursion, a chronic betrayal. Argentina’s La Nación describes Glaxo, Ronsino’s first novel to be translated into English, as “a machine with perfect gears,” and surely Glaxo is the road, the link road, through a landscape of individual and cultural trauma.

Which is not to say testimonial writing is the same as confessional writing. Ronsino’s characters actually confess very little of their paramount concerns, often revealing more through circumvention. The excerpt from Rodolfo Walsh’s Operación Masacre, which serves as Glaxo’s epigraph, not only calls forward the sufferings of Argentina’s Revolución Libertadora, it carries with it the literary tradition of testimonial fiction. Operación Masacre, a book about the José León Suárez massacre of 1956, in which Buenos Aires police rounded up and shot a group of men they suspected of having been involved in a political uprising, is considered by some critics to be the first “nonfiction novel,” predating Capote’s In Cold Blood by nine years. Ronsino’s Glaxo uses similar “testimonial” strategies: it is fiction about tension that arises from half-buried injustices, but fiction with crucial ties to Argentina’s recent political history. The novel’s path is not dictated by a single character (there are four points of view divided into four sections) and is not delineated by time (the sections are non-chronological). The path instead defines itself via a mounting dread, psychological steps that force the characters, no matter how close to or far from the novel’s unspoken ground-zero trauma they may be, to implicate themselves in that trauma again.

ardemann’s testimonial begins the novel in the fall of 1973, when the wounds become irrevocable. Glaxo is a town with Vardemann’s barber shop at the end of the street and Souza’s butcher shop on the corner—opposite the Glaxo factory, the Barrios household, and the remains of the Ace of Spades bar. At times, the repetition in Vardemann’s narrative seems the small talk of a poky town, facts repeated word-for-word because of a lack of new information: “This is the second time it has rained since the work team has been pulling up the tracks.” But these daily observations also reveal the unsaid, observations that threaten to trigger a corrosive memory: “the smell of grilling meat enters the barbershop, coming from over in the clearing of the cane field, and it awakens in me a decrepit, sharp anguish.” There is not only familiarity in Vardemann’s repetition, but also evasion. The same factory machines of the last generation still hum, punctuated by “the blackened metal drums, burning with fires that never seemed to exist by day, with the fires burning that don’t seem to be there during the day.” A deep disruption has replicated itself within Vardemann’s waking and nighttime hours, and as the dismantled trains and their obsolete tracks become a part of the town’s past, so does the unspoken become more unstoppable and recovery more distant for the town’s citizens. Isolation and denial, in other words, simmer under the “primitive quiet” of Glaxo.

ardemann’s testimonial begins the novel in the fall of 1973, when the wounds become irrevocable. Glaxo is a town with Vardemann’s barber shop at the end of the street and Souza’s butcher shop on the corner—opposite the Glaxo factory, the Barrios household, and the remains of the Ace of Spades bar. At times, the repetition in Vardemann’s narrative seems the small talk of a poky town, facts repeated word-for-word because of a lack of new information: “This is the second time it has rained since the work team has been pulling up the tracks.” But these daily observations also reveal the unsaid, observations that threaten to trigger a corrosive memory: “the smell of grilling meat enters the barbershop, coming from over in the clearing of the cane field, and it awakens in me a decrepit, sharp anguish.” There is not only familiarity in Vardemann’s repetition, but also evasion. The same factory machines of the last generation still hum, punctuated by “the blackened metal drums, burning with fires that never seemed to exist by day, with the fires burning that don’t seem to be there during the day.” A deep disruption has replicated itself within Vardemann’s waking and nighttime hours, and as the dismantled trains and their obsolete tracks become a part of the town’s past, so does the unspoken become more unstoppable and recovery more distant for the town’s citizens. Isolation and denial, in other words, simmer under the “primitive quiet” of Glaxo.

Bicho Souza’s narrative, told from the year 1984, is no less recursive—more so, as over twenty years have passed since the unspeakable incident the novel circles around. There’s a duplicity throughout Souza’s narrative, his nostalgia forced to redefine itself amidst the ugliness of fact: Lucio Montes, a friend from the old days, becomes an “invasion”; La Negra Miranda, Folcada’s wife, inspires fond memories of the Ace of Spades bar, but also “to name La Negra Miranda is like naming a ghost”; a waiter at the bar is at once a character from a film Souza enjoys and a killer. Last Train from Gun Hill, the American Western film Souza has recently rewatched, reminds Souza of the pretend gunfights from his youth, but the film also carries layers of betrayal and loss, reminders of old wounds that won’t heal.

Souza’s repetition of the line “You’re no more than the reflection of the toes on your feet” is a symptom of this disturbed nostalgia. The first time he thinks the words, Souza is “moved.” The second time, he thinks the line “obsessively,” he holds onto its goodness, and the third forces Souza to recall ugliness—an image of Folcada. Souza mentally bargains over a loss from twenty years prior, suggesting a truly unsettling trauma—he grieves strongly enough that he must bargain obliquely, by way of the film: “if that woman, who is traveling to visit her family, if she hadn’t attacked Anthony Quinn’s son by beating his face with a whip, perhaps none of what happened next would have occurred.” Even as Glaxo moves away from this unspoken event, further forward in time, the tension accelerates the dread of testimonies to come: “he captures me again, the bastard, with his story.”

Miguelito’s narrative begins in the summer of 1966, closer to the event, yet still seven years after the fact. His testimony could fall directly into the “B” criterion of the DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Vardemann has returned from prison, which triggers Miguelito’s various self-defenses. Immediately upon seeing Vardemann at the train station, Miguelito prioritizes certain thoughts over others. He victimizes himself by seeing his own death in Vardemann’s arrival, which leads to other thoughts of death—he admires himself for looking at the deaths of others, for that kind of bravery. Miguelito also reasons away his silence: “That’s why I prefer not to go around saying such things…you know that no one will believe you…People are shallow.” The premise is repeated by Folcada later in the section, and allows Miguelito to foreground memories of the good times (his father, his boyhood friendships, La Negra Miranda), while veering away from certain dangerous topics. Miguelito might see himself as “summoning the courage to explain,” but what is conveyed is deep-reaching regret and a dread of vengeance, the fantasy of a Western showdown coming awfully to fruition.

Which leads to the final testimony: Folcada’s narrative, written in the form of one unbroken paragraph, told from 1959, the time of the incident. The expectation is that here we will finally find the “A” criterion from the PTSD DSM: the point of origin, the catastrophic event, the witnessing. It is what the novel has been developing towards, and what the characters’ dread over the ensuing years has been built on. But when Glaxo might deliver the characters from the mist of dread and denial, allowing confrontation and perhaps even acceptance, more crimes come to light. “Betrayal is the foundation of war,” says Folcada, and Ronsino is writing to that very foundation. Even as Folcada freely admits violence, more dreadful wrongs are alluded to. He mentions the “Suárez business” in relation to his past work as a Buenos Aires police officer, and with an epigraph quoting Walsh’s Operación Masacre, the character can only be referencing involvement in the José León Suárez massacre of 1956. Rather than exposure therapy, Folcada’s narrative instead reenacts the trauma—not only the trauma that occurred in Glaxo, which the other three characters have referred to throughout the novel, but also the trauma of the José León Suárez massacre. In this way, Glaxo withholds while it testifies, like a knot tightening. Ronsino replaces the dread his characters feel with another type of horror, a reoccurring wound inflicted by domestic unrest and political upheaval, the real and extensive violations in Argentina’s recent history.

Thea Prieto’s short fiction has appeared at The Masters Review, NAILED Magazine, and in other publications, and she was a finalist for Glimmer Train Press’ Short Story Award for New Writers. Between writing and editing, she teaches at Portland State University.