Craft Q&A

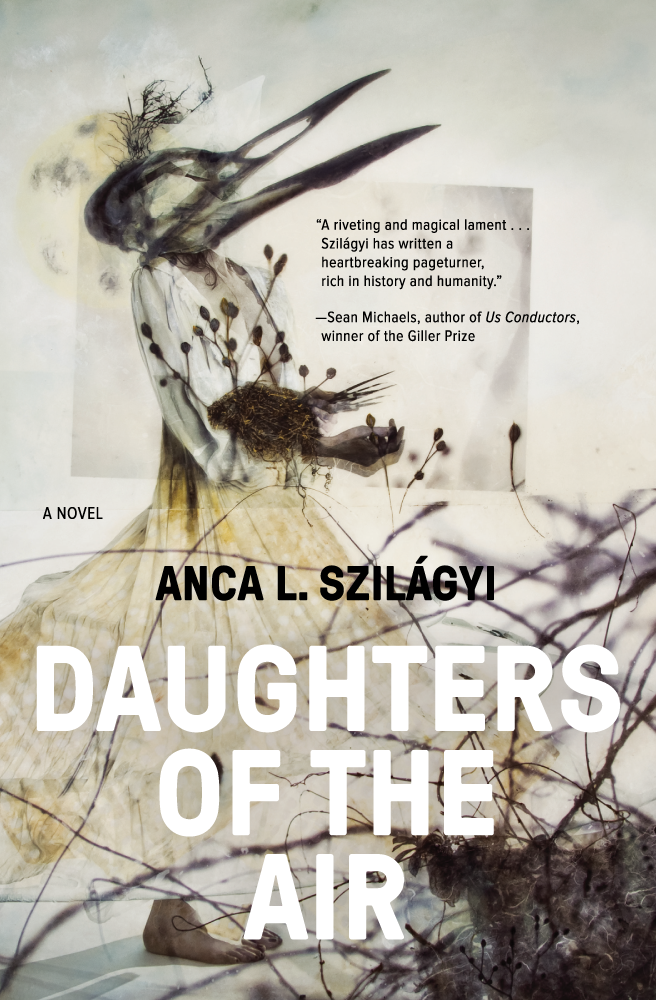

Anca L. Szilágyi’s debut novel, Daughters of the Air (Lanternfish Press), is the story of Tatiana “Pluta” Spektor. Tatiana is a mostly happy, if awkward, young girl, until her sociologist father is disappeared during Argentina’s Dirty War. After being sent to a Connecticut boarding school by her grieving mother, Pluta runs away to the streets of 1980 Brooklyn to contend with the unsettled tragedy and to figuratively and literally spread her wings. Pluta’s simultaneous estrangement and coming of age creates a haunting tale of personal devastation wrought by political repression. Propeller published Szilágyi’s story “Old Boyfriends” in the fall 2013 issue, and her writing has also appeared in publications including the Los Angeles Review of Books, Electric Literature, Gastronomica, and Fairy Tale Review. The Stranger hailed Szilágyi as one of the “fresh new faces in Seattle fiction.” —Thea Prieto

Thea Prieto: Daughters of the Air takes place across two timelines, one in 1978 and the other in 1980. These two timelines eventually converge and your characters converge, as well, though in unexpected ways. To begin our conversation, could you tell me a bit about where Daughters of the Air began for you? Did you discover your parallel storylines early or later in your writing process, or how did this narrative take form?

Anca Szilágyi: The earliest seeds of the book are Pluta’s dreams, some of which came to me while recovering from surgery in 2001, though they have since been altered and expanded upon. At some point in the years following, I began to worry about the rhetoric of the War on Terror; there seemed to be some troubling similarities with Argentina’s Dirty War, which I had first learned about in 2003, via Anne Carson’s novel-in-verse Autobiography of Red. The similarities between the Dirty War and the Holocaust were also alarming, and I wanted to understand how such a nightmare could recur in more recent history. Meanwhile, I kept picturing a strange teenage girl alone in Gowanus, Brooklyn, a gritty neighborhood where I took dance classes in high school in the late ’90s, in a former soap factory. Eventually, the Dirty War became part of the girl’s history. The first draft of the novel was written chronologically, but I later realized it would be more compelling to alternate between her running away and her reason for running away—the unresolved tragedy of her father’s disappearance.

Prieto: Fascinating, and remembering Autobiography of Red now, Anne Carson’s protagonist is Geryon, which is of course a reference to a Greek mythological creature with wings. In both Autobiography of Red and Daughters of the Air, wings are correlated with a difficult kind of self-actualization. Barring any story spoilers about the fate of Pluta’s wings, I’m interested to hear how you envisioned the path of Pluta’s self-actualization in Brooklyn.

Szilágyi: Oh gosh—how to avoid spoilers here. It’s partial, I would say. It’s very difficult and partial, like any adolescent’s self-actualization, but under extreme duress. Though there’s hope in it, too.

Prieto: There’s a narrative path as well, and it shifts in point of view, not only between timelines but also within sections, within paragraphs. The point of view switches between characters and in register as well, third person being the primary register, with Pluta’s dreams in first person, interior dialogues often switching to second person, and an authorial point of view emerges in the first paragraph of the epilogue. Tell me a bit about your point of view decisions for Daughters of the Air. Another way of asking this question—why would a constrained point of view, or a broader authorial point of view, have hindered the narrative?

Szilágyi: I think I broke every “workshop rule” about point of view! I felt it was important for the narrative intelligence to have access to the minds of each family member within sections to show their unity as a family, even as they have trouble communicating. I’d hoped that doing this would also amplify the feeling of isolation in chapters when Pluta and Isabel are all alone; omniscience could have taken away the sense of isolation readers might feel alongside them.

I believe dreams are a first-person present kind of experience, so that shift is really about accessing greater psychic intimacy and immediacy. The shift to second person in interior dialogue also registers a deeper intimacy, albeit in waking life, and with a sense of self-loathing. The epilogue’s wider point of view finally allows for some historic context and thus a reprieve from the burden of not knowing.

Prieto: I agree, and I felt that sense of isolation you mentioned, when I knew your characters shared a grief and a fear that remained unspoken between them. As a reader, it was quite tragic to witness. The shifts in point of view also make the different plummets in the epilogue—including the plummet from a detached, historic context into each character’s individual, lived experience—especially harrowing.

Szilágyi: Thank you—I was really working toward making the plummets as visceral as possible.

Prieto: Much goes unspoken by Pluta, especially to her mother, and of course, between them, much is unsaid about the Professor. I believe this individual and communal censorship underscores the many other forms of communication in Daughters of the Air, the missed or one-sided phone calls, long distance or tampered-with letters, mysterious packages, séances. How are your characters, who are contained in a setting of political repression, and you, the writer constrained by that history, dependent on these alternate forms of communication?

Szilágyi: When censorship prevails, whether imposed externally or internally, messages still need to seep out, one way or another. I was really moved by Ricardo Piglia’s novel Artificial Respiration, which was a critique of the dictatorship and published in Argentina in 1981, a dangerous feat. It is a formally challenging book, and the critique is buried in many narrative layers that look to other dictatorships in Argentina’s history. There is an imagined encounter between Kafka and a young Hitler that I found enormously affecting. The epigraph I included from Piglia’s novel in Daughters of the Air speaks to the need to look for those repressed messages wherever one might find them.

Prieto: I noticed in your acknowledgements you thank the Museum of the City of Buenos Aires, and you evoke very rich and immersive settings throughout Daughters of the Air. I’m curious to hear about the level of research that went into writing about Argentina’s Dirty War and New York City in the 1980s.

Szilágyi: The research was intensive, particularly regarding Argentina. I spent many years reading journalism, memoirs, and histories, not just of the Dirty War, though that was the focus, but also the country’s general history, and certain related topics, like Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish immigration. After I wrote a first draft, I was able to go to Buenos Aires for two weeks, which, as you can imagine, was enormously helpful. My husband came along, and with his better Spanish-speaking skills and my better Spanish-listening skills, we made for a good team. We signed up for a wonderfully extensive walking tour through a volunteer organization called Cicerones. As a result of that tour, I changed the neighborhood the Spektors lived in. Initially, I’d chosen the Jewish neighborhood of Once, but as soon as I was there I realized Isabel would not be a fan, so I asked the guide about other Jewish areas to explore. In Belgrano, I found just the house for Isabel. I met with a few people who’d lived through the Dirty War, witnessed the weekly Mothers of the Disappeared protest in front of Casa Rosada, and pored through glossy magazines in the library at the Museum of the City of Buenos Aires, which gave me a lot of insight into popular culture at the time and a vivid picture of life simply going on, despite everything, with no mention of the ongoing repression.

“I’m a food-obsessed writer and imagine a manuscript as a broth that gets richer with each book added.”

I grew up in New York City in the 1980s, so I have a more immediate experience with that time and place. But I loved reading up on the Gowanus Canal, an important setting in the book—I am just now digging into Joseph Alexiou’s 2015 history, Gowanus. I pored over old subway maps and the like to get certain nitty gritty details right. Websites like Forgotten New York and Ephemeral New York were also good resources. I also had fun researching communication technology from the time, learning about early fax machines and whether a private detective would have had a walkie-talkie and so on.

After the bulk of my research was done and I had solid second draft, I immersed myself in Argentine fiction as well as books set in New York in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

Prieto: Any Argentine or New York-based fictions you would suggest? In my experience, writing historical fiction feels like creating a new artifact out of preexisting artifacts, both fictional and nonfictional. Are there a few primary artifacts you would suggest your readers check out before, after, or while reading Daughters of the Air?

Szilágyi: Oh, I love that metaphor of building artifacts from artifacts. I’m a food-obsessed writer and imagine a manuscript as a broth that gets richer with each book added to the mix. I already mentioned Artificial Respiration. Another book from the era is Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel Kiss of the Spider Woman, set in an Argentine prison and told almost entirely in dialogue. Alicia Kozameh’s Steps Under Water, an autobiographical novel based on the author’s experiences as a political prisoner, also stuck with me. Liliana Heker’s metafictional novel The End of the Story also explores the experience of being a political prisoner, but this time through the perspective of a writer trying to reconstruct her friend’s experience. Finally, Marcelo Figueras’s novel Kamchatka is about a ten-year-old boy whose family must go into hiding to avoid being apprehended. The game of Risk is a motif in the book, wherein the region of Kamchatka stands in for the need to distance oneself, emotionally, from traumatic experiences.

Two New York-based books gave me a nice sense of the city before my time: Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids and Binnie Kirshenbaum’s An Almost Perfect Moment. The latter is set in a part of Brooklyn that doesn’t factor into Daughters of the Air at all, but it was a delightful, funny story, and so a pleasant reprieve from the heavier stuff.

Anca Szilágyi is a Brooklynite living in Seattle. Her fiction appears in Gastronomica, Fairy Tale Review, Washington City Paper, and elsewhere. Her nonfiction appears in Los Angeles Review of Books, Electric Literature, Jewish in Seattle, Kirkus,and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships and awards from Made at Hugo House, Jack Straw Cultural Center, 4Culture, and Artist Trust. The Stranger hailed Anca as one of the "fresh new faces in Seattle fiction." Her debut novel, Daughters of the Air, is forthcoming from Lanternfish Press in December 2017.

Thea Prieto reviewed Hernán Ronsinso’s newly-translated novel Glaxo in the spring issue.