Reading Lines

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself…

—Coventry Patmore

VIRGINIA WOOLF SAID that it was the woman writer’s job to kill the “Angel in the House,” Coventry Patmore’s shimmering chimera of fantastical femininity. The poem is a fluff piece fit for middlebrow tastes at best, but for whatever reason, the idea caught our imagination and stuck around for decades, alternately torturing and pacifying us with treacle. A feature of the English Novel since forever, the morally superior woman is, to be honest, kind of comforting, maybe because we still like to fancy ourselves capable of transforming beasts into princes without doing much besides silently radiating virginity. We figured by now these Clarissas and Pamelas had peaceably rotted into fairy dust, along with their dark, sexually voracious, hysterical sisters drawing otherwise good men to psychological ruin and bankruptcy. I hoped so too, or hoped they had at least slunk back into their regency novels, along with the wolves and roués (and reformed wolves and roués) to throw themselves on chaises and die of consumption or get married at long last, forever and ever amen.

But lately, as I watch the latest internet parade of public apologies for sexual misconduct—these gleefully tawdry stories of girls brought low by the lusts of powerful men—I’m not so sure. The motivations behind these stories seem suspect, although I doubt I’m supposed to say what I actually think—which is that a late and very public revelation is only a good strategy if the circles you run in are content worthy. For the rest of us, time is up about two seconds after your boundaries are violated.

And look, I know that’s not always possible, but plenty of times it is, and where I grew up, those deer-in-the-headlights girls, those hesitating, eager to please types, their lives were ruined in ways that no one reading Jezebel wants to hear about. No triumph, no survivor stories, just crushed into dirt, usually more than once, and their families with them. A working class nobody who can’t protect herself with meanness or resourcefulness in the moment also can’t wait for HR or a think piece to save her. She may only have herself, and she can’t afford to see her institutions as in loco parentis.

“We may have overlooked that other patriarchal problem, the myth of the good girl, the angel, the innocent victim traumatized by our bloody sexual revolution.”

Stuck sorting out the (admittedly more urgent) patriarchal problem of male sexual entitlement, we may have overlooked that other patriarchal problem, the myth of the good girl, the angel, the innocent victim traumatized by our bloody sexual revolution, unable to survive this cruel world without chaperones. I think we might still in our secret hearts believe in her. She’s Anastasia Steele and Bella Swan, and we can’t get enough of getting rescued, at least in our imaginations. She makes us doubt our own ability to navigate our lives, to trust that we can manage the gropers, the cat calls, the white house, and much, heartbreakingly much, worse. Instead of strength, she has virtue, and virtue doesn’t keep you safe.

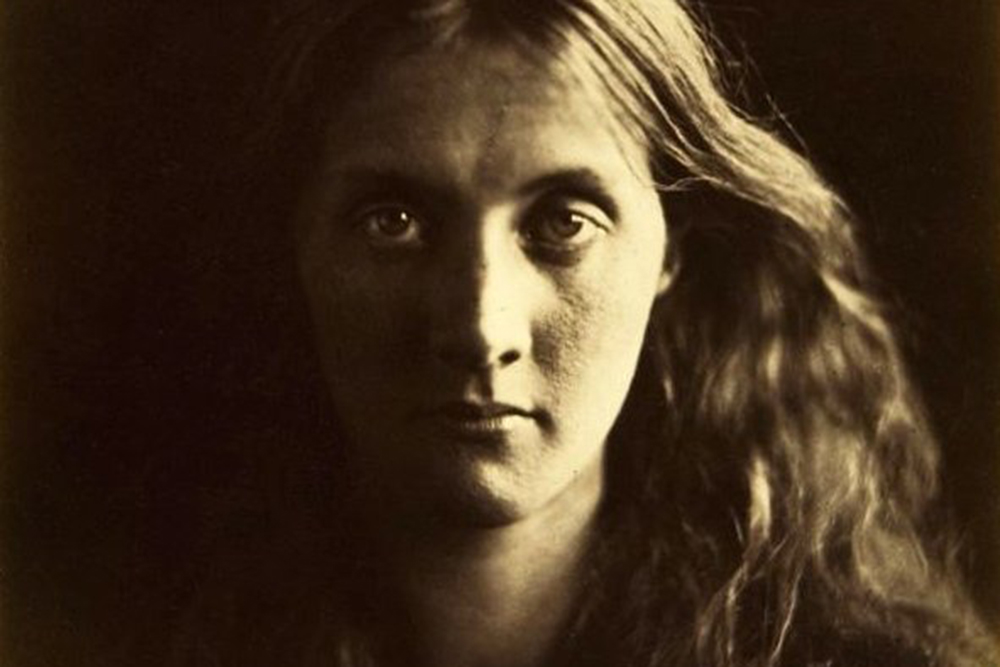

Julia Prinsep Jackson. (Julia Margaret Cameron, 1867.) Cameron’s niece, mother of Virginia Woolf.

Most adult women I know in real life are pretty tough, and capable of real mayhem, especially when they are righteously pissed, generally, about the state of things. When you (I mean me) feel powerless publicly, you might be more likely to exploit what power you do have privately. And despite our physical and systemic vulnerabilities, women do have sexual power, though we often won’t admit it. We are the ones biology gifted with the job of mate selection, and none of us are doing any public apologizing, even though we probably owe a few. Like Sade says of his wrathful anti-heroines, “one is never so dangerous when one has no shame, when one has grown too old to blush.” More of us should be dangerous.

Admitting you can do damage may be the first step toward empowerment. So here I go—in the interests of sexual equality and also to poke a sharp stick at the contemporary angel:

I Hereby Issue a Public Apology for My Lack of Sexual Integrity

I’m sorry for the derisive nicknames I gave to insensitive or awkward lovers, to make my friends laugh, which then followed them forever.

I’m sorry for revealing embarrassing details of a man’s anatomy or sexual habits if he hurt my feelings or my pride.

I’m sorry for the times I purposefully emasculated someone because I felt cornered.

I am sorry for that drink in the face.

I’m sorry for the times I seduced someone I didn’t care about, for ego validation or vengeance against another.

I’m sorry for the times I flirted casually with another’s sweetheart, or when I myself was taken, therefore creating distrust or chaos, just because I was bored.

I am sorry for the times I broke someone’s heart because I lied to myself about my feelings, or because I was too lazy to do the right, difficult thing.

I am sorry for the times I was inconsiderate because I bought the convenient lie that men don’t have feelings, or that they would rather get laid than treated like a person.

I am sorry for the times I was cruel because I was mad, at my dad, at the world, at the unfairness of it all, and took it out on some poor dude who was just trying figure it out like I was.

Ok, that was rough. But the other night I dreamed a recurring dream, that I murdered someone years ago, and the body is about to be discovered under the basement dirt. I wake up sick with guilt and shame, relieved to see my sweetheart safe asleep beside me. Maybe the reformed wolf is me, and he’s the angel in the house, “casting his best” and all that, though I’m sure he has his own long list of amends to make. Nobody is really pure, not even children.

Wendy Bourgeois is a poet and writer. In the winter 2018 issue she discussed how beauty is not democracy.