Craft

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

THIS IS the second of a three-part interview with writer James Salter. Readers who haven’t read Salter’s new novel, All That Is, may wonder about a discussion that arises at the end of today’s piece regarding the book’s main character, Philip Bowman. All that is necessary to know is probably contained in the jacket copy: “In this world of dinners, deals, and literary careers, Bowman finds that he fits in perfectly. But despite his success, what eludes him is love. His first marriage goes bad, another fails to happen, and finally he meets a woman who enthralls him—before setting him on a course he never could have imagined for himself.” —Dan DeWeese

DeWeese: As you said, the frame of All That Is is the frame of your own life. Toward the end there’s a passage about how Bowman is aware that the novel’s place in the culture has been diminished—and All That Is ends sometime in the mid-1980s. Have you noticed changes in the publishing industry over the course of your career that you would point to as being fundamental?

Salter: I think these are well known, and very obvious. There are a lot of small presses, but they’re mostly, I don’t want to say insignificant, but quite small, almost local. And the other publishers have all become conglomerates, and when you go to the publishing offices—somebody said this last night—you go to the Condé Naste office and each floor of the building is an identical floor done the same way, but it’s a different magazine with a different mission. So on one floor is Vanity Fair and on the next floor is, I don’t know, National Geographic—that’s not one of theirs, but it’s like that. And in the publishing houses, it looks different, the architecture is different. They all have modern cubicles. The most important ones have good views. They argue a lot about who gets which office because that one looks out at a wall, this one looks out at the river. The rest of the people are in a pen—as in television, whenever you see a business there are always people in these little enclaves, they have a computer, a picture of their dog and wife on the wall. So it’s not the same. Publishing used to be a good deal more idiosyncratic, a good deal more old school, naturally, and was owned by individuals in many cases who were able to exercise their instincts—what they wanted to publish. That’s not quite true anymore. It is true you can publish what you want, but the bottom line is very, very important—these are big corporations, so the financial people have a lot to say about what’s going on. That was always a consideration in publishing—you can’t go on just publishing books nobody buys, who’s going to pay all the salaries?—but it’s different, it’s just done in a different way. Just as I think probably Wall Street is different than it used to be, although I know less about that.

Yes, so I would say it’s changed. For instance, Pat Strachan the other night, she said that if I brought in a book of fiction, male fiction—she said I couldn’t propose a book of mid-list fiction. This is an experienced editor, and she happens to be at Little, Brown, I believe. They don’t want to hear that. They’re publishing, naturally, young people’s fiction. The readership is largely women, always has been, but I think more significantly now—my impression is that it’s more definitive. Men will read books about politics, history, sports, movies, all of that, but the fiction generally belongs to women. I don’t know—that may be wrong, but that’s my impression.

DeWeese: Do you feel like these changes have affected your own writing career, or are they only affecting younger writers?

Salter: Well, they can’t affect me now, because mine is over, or virtually. I think young writers are affected by this, naturally. You’re inclined to take your own experience and use it as the norm, even though it may be really very far from everybody else’s. Somebody said to me, I think a schoolmate, said, “My uncle’s an agent.” So I went to see an agent named James Brown. I mean, I was 21 years old and I’d written something. And he saw me. He said come in, and talked to me. Now, I don’t remember whether he read it or not. In any case, it wasn’t published. And the next agent was very much the same. They read manuscripts that came over the transom, as they say. They were a couple of former magazine editors who’d become literary agents, so they read stuff and he read this and said, “Yeah, all right, let’s see”—he was an old school fellow, it wasn’t that casual, he was smoking a pipe—he said, “So-and-so might like this.” That kind of thing. But it seemed quite easy. Now I constantly hear, “How do I meet an agent? How am I going to get an agent?” So my impression is it must be a little more difficult than it used to be. But again, I’m only going on my own experience.

DeWeese: Another industry that I feel has changed in similar ways is obviously the film industry. In other interviews you have somewhat dismissed your years writing films, which hurt my feelings a little bit.

Salter: [Laughs.]

DeWeese: Because when I saw Downhill Racer I thought, This was written by someone who understands me. [Note: The interviewer has already written about his admiration for Downhill Racer.] And then when that someone later said, “Oh, it was all a disappointment…” You worked in film during an era that is now considered one of the more important eras in American filmmaking. Are there positive things you took away from that work? Or do you still mostly feel it was a frustrating time?

Salter: Well, I’ve adopted a tone of bitterness. Of course it was important to me at the time. I thought it would turn out better than it did, I mean for me personally. And having decided, “It’s not going to turn out any better,” anything—

DeWeese: By better, what do you mean?

Salter: I wanted to make a good movie. I guess everybody does, there’s nothing significant in that, nobody starts out trying to make a bad movie. But I wanted to make a movie with a terrific director and have people say it’s a knockout, simply wonderful. And it never happened. It could have been a number of things. It just didn’t happen, luck didn’t fall your way, or it could be from my own shortcomings as a film writer, it might be a combination of both—whatever it is, it didn’t happen. I guess I wouldn’t still be doing it now, because nobody would hire me at this point, you have to have a pretty solid reputation to keep writing when you’re past whatever it is—forty, probably. No, I love films, not as much as I did. And I don’t see them as much as I did. And the more I don’t see them, the more important they seem to be.

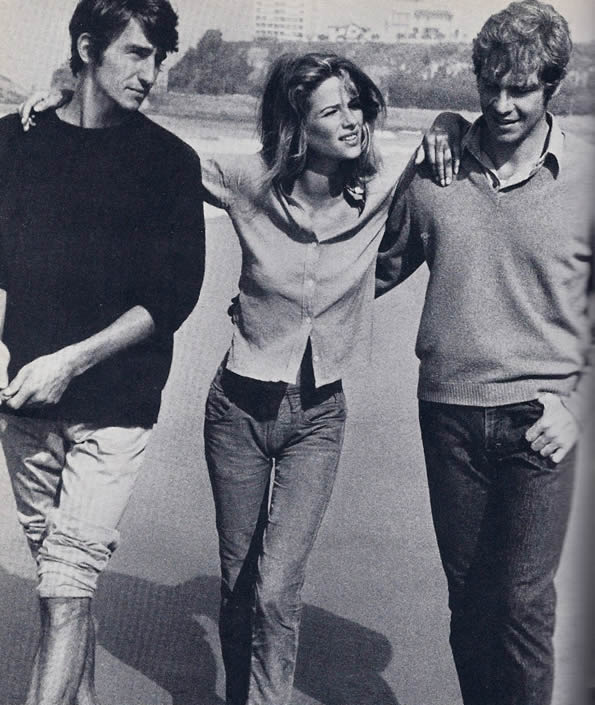

Salter’s directing credit: Sam Waterston, Charlotte Rampling, and Robie Porter on the set of “Three.”

DeWeese: There’s this popular narrative of American film from mid to late 60s up through mid to late 70s, that this was a golden era that was then squashed by studios becoming corporate or part of international corporations. As someone who was working in the industry in those years, are there aspects of that narrative we are getting wrong, or oversimplifying or overlooking when we fetishize this period as a beautiful moment?

Salter: I think you have to wait a little longer. Wait another twenty years and see how all that goes. Films go in kind of cycles. Before Star Wars there was no Star Wars, and there was no multi-billion dollar Lucas industries—in fact he made a couple of failed movies—so that changes everything right away. Before The Godfather there was no Godfather. I think it’s incidents—they change everything, and they change the wave of what’s going on. But it seems to me there are always big films and small films. And it’s the balance, the attention of the public is shifting a little bit. There’s always an audience for big films because there are all those people who like to see the car chases and so forth. But then there is always a sophisticated audience, so to speak, for a different kind of movie. I think that’s going on pretty much the way it was. The numbers have gotten, it seems to me, frightening—I can’t imagine. I talked to Steve Gaghan, he was the writer of Traffic, he’s a literary kind of guy, and of course his connections came through Sundance—a lot of people’s early movies, the scripts were worked there, they made connections there, then maybe Telluride or one thing or another, that’s the way he started. So now he’s trying to make another movie, he won an academy award for the script [for Traffic], he’s seeking to make another movie that he wrote, and he needs $30 million. Well I know that there’s been inflation, but even cutting it to ten percent of it, that’s not what a film cost then—it didn’t cost three million dollars. And the big films, of course, cost a hundred million, or whatever they cost. So in that league, that seems a little different to me. But of course people are always sneaking in, in the gaps between this and that, some clever guy—like Soderbergh, I guess. It’s the same story, retold with different examples, different figures. As far as being golden, well—it had its films, but today has today’s films.

DeWeese: To get back to All That Is, you have an ability or willingness to follow characters into dark places—to have characters occasionally make decisions that might upset readers. There are times I felt a tone that almost moves toward something a little bit gothic. I’m wondering what kind of role you feel…the words I wrote down are malevolence and revenge. But what kind of role do these darker impulses play in your fiction?

Salter: Well…I can’t think of any particular dark impulses. There are infidelities. There are some smarmy people—not often. But I don’t think they have big significance. They’re just—that’s what I was writing about.

DeWeese: I guess I’m thinking in All That Is, when Bowman takes Christine’s daughter to Paris. And then there’s a short story, I’m sorry, I can’t remember the title, there are two men traveling through Europe together, and one of them—

Salter: “American Express.”

DeWeese: Yes. These are darker stories—maybe it’s wrong to call it darkness. These moments often have a sexual element. I guess that’s what I was thinking of, but maybe you don’t think of it as dark.

Salter: Well, I knew in “American Express” what is happening. But of course it’s not just sex, that was just the ultimate incident, that’s where we last saw them. When we first saw them all they had done was a highly irregular, immoral act of stealing a client from the firm they were working for. One is no worse than the other, in a sense. I just meant that to be a picture of two men and what happened to them when they took the wrong road, so to speak. They took the wrong road but it wasn’t that bad, which is what happens, yes? If you’re the first one stealing and get out the door, you’ll be all right—which is essentially what happened in that story. They’re both sons of lawyers. They were lawyers and sons of lawyers. And I guess, I don’t know, lawyers seem a logical villain to me.

DeWeese: [Laughs.] But Bowman’s not a lawyer.

Salter: No.

DeWeese: The episode in which he takes Christine’s daughter to Paris, it’s not quite the same as “American Express,” but it’s similar in terms of taking a young woman in a way that I think most readers would say, This is not the right—

Salter: Not the right way to behave.

DeWeese: Yes.

Salter: Well—I don’t feel that strongly about it. I’d say it’s the way people behave, and whether it’s right or proper doesn’t have much to do with it. [Pause.] Also, it has some voltage.

DeWeese: What do you mean by voltage?

Salter: The situation has voltage. As you said, the impropriety of it, the feeling that a lot of people—I don’t know how many instinctively—have about it, it has some power. It’s not just a casual incident. That’s one thing. And secondly, there’s the question of what is your reaction, and how much of that is what you feel should be your reaction? How much are you really thinking, and how much is what you are “supposed” to be thinking? This is an element that is in play all the time when you’re writing. Are you writing what you really know and what you really feel? Or are you writing the “correct” thing, are you obeying social and literary norms?

Rachel Greben: When I was reading All That Is, right up until that incident I was thinking, What’s going to happen with Bowman? And out of the blue he does that. And I remember saying, “I don’t know what to think about this character now. He just made me really mad.” But I love how you give the reader opportunities to be puzzled sometimes, and to make their judgment on their own. And you give it time.

Salter: What did you finally decide?

Greben: At the end?

Salter: No, I mean after the dust settled a little bit.

Greben: With Bowman, I understand what he did. Also it made me mad, because I understand what she would feel like. And the whole situation with the mom’s daughter, on a whole different level—you know, I have a daughter too, so it makes me—

Salter: Naturally.

Greben: The hair on my neck rose. It did make Bowman interesting there, because you didn’t expect it, and you were ready for something. So although I don’t approve of what he did, I really enjoyed not having it carved out exactly what I was supposed to think about this character. I think another character says that about Bowman at some point: “Watch out for him.” And we’re like, What? A lot of that resounds with normal experience—you don’t know everything about people, you can’t know them. That’s part of what makes it interesting and scary. I enjoy the challenge as a reader.

DeWeese: Do you ever worry that you’re challenging readers too much? Or is that not something you worry about?

Salter: Well, if you go too far—I don’t know. I suppose I should feel that’s their problem. But when you hear comments and you realize the story didn’t come through, they didn’t understand, they didn’t read it carefully enough—skipped over a very important phrase here, or a word—I suppose you have to think about that. Are you assuming too much about the ability or interest of the reader? I’d say it crosses your mind, but I don’t know how important it is.

DeWeese: When you say the ability of the reader, what kind of abilities are you thinking of?

Salter: Well, the ability of the reader to read the words, and not just to be going down the page. To be listening. A reader who enjoys reading—I feel that I can do well with such a reader. The readers who put less into it and who are a little deaf, really, to the sound of things, and the nuances of things—I feel they’re missing it a little bit.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

James Salter’s novels include A Sport and a Pastime, Light Years, and Solo Faces. His story collection, Last Night, was published in 2005. A collection of his non-fiction, There and Then: The Travel Writing of James Salter, also appeared in 2005.

Dan DeWeese is the author of the novels Gielgud and You Don’t Love This Man, and a story collection, Disorder.