Craft

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

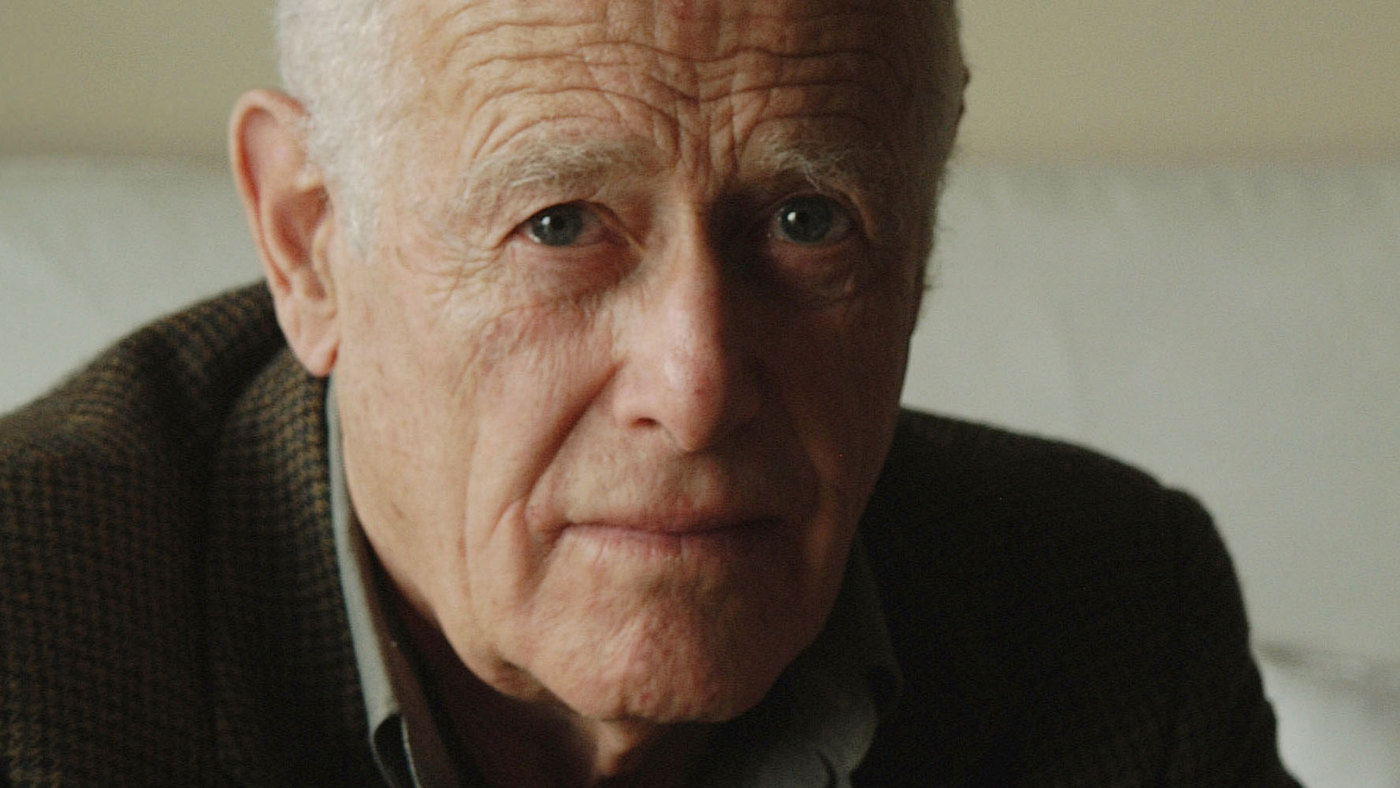

THIS IS the last of a three-part interview with writer James Salter. The interview was conducted October 4, 2013, in New York. —Dan DeWeese

DeWeese: There’s a certain kind of novel that presents a character’s behavior and then quickly explains the character’s behavior psychologically.

Salter: Yes.

DeWeese: Your writing avoids that in ways I think are very compelling. What I wondered is whether drafts you write have some of that and you excise it, or whether you conceive of stories in a way that doesn’t involve this contemporary style, where the story exists for me to psychologically analyze a character.

Salter: I try not to write those things to begin with. And if they show up anyway, I’m likely to take them out. I prefer not to have that—I prefer to have the story and the people speak for themselves, and neither to judge nor explain them too fully, too energetically.

DeWeese: I teach, so students sometimes ask this, but it also comes up among writers—what the word “literary” means. The term’s obviously baggy, and yet it’s important. I guess I’m asking because I feel it’s related to the ability not to explain the story, to excise the psychologizing. I’m wondering what you feel the difference is between a literary exploration of the world versus something we would decide is not literary.

Salter: There’s not a good dividing line. Because non-literary stuff may turn out to be very literary, you just didn’t know it—because that’s the way it came in, so to speak.

DeWeese: What kind of qualities would it have that would make it literary?

Salter: The quality of enduring. People like it and want to read it. In its essence, what makes it literary—well, it never really becomes “literary,” but it does become part of literature. It may not be “literary.” Is Henry Miller literary? Not really. I mean, he’s carrying on, he’s got a great poetic gift, he’s very full of energy, he’s a little batty—not really, but he’s out there. I don’t think it would have been called literature when it first came out in the early 40s, I suppose, and was smuggled in as pornography—not really pornography, but steamy, or whatever the word is. But now we don’t think of it that way. I don’t think we do. We say, That’s remarkably good. People still—I assume this is true—people still like to read it. I do, I think he’s a wonderful writer.

You know, there are three writers whose books are not on the shelves at the Harvard Book Shop. They don’t keep them on the shelves, they keep them behind the cash register, because they kept being stolen by the students, shoplifted: Burroughs, Kerouac, and Charles Bukowski. So that’s a literary statement, in a way—they want to read this. They continue to want to read it. It’s never disproven or demolished.

DeWeese: Are there writers you value that aren’t part of the contemporary conversation about literature, that you think have been overlooked?

Salter: Oh, yes. But I mean, I like them, but there may be very good reasons for them being overlooked. There’s a French writer, fairly well known to be on the lunatic fringe, called Pierre Guyotat. He served in the army in Algeria, and he’s a wild and feverish homosexual, and his books, I think, are incredible. But nobody would ever read them, and I wouldn’t give them to anybody that I didn’t know would like them—I wouldn’t propose it. There are others, he’s not the only one. He comes to mind immediately because he’s a singular writer. Destined to never become known.

DeWeese: Any others you can think of?

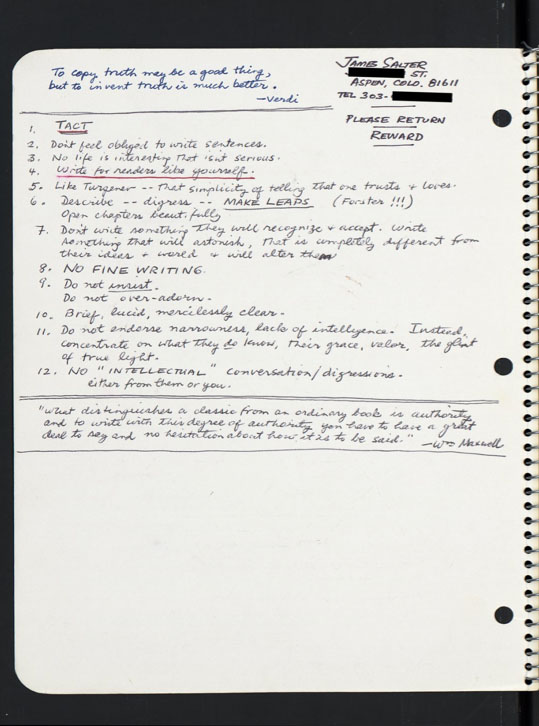

Salter: Well, the thing is you don’t often come across them, because often they’re not published. I’ve had writing students who I thought had a real gift, but nothing became of them. They didn’t go further. Or they didn’t realize it themselves, they didn’t know what was really good about themselves. It’s hard for them to know. What I always found is they’d written something really pretty good, but sections of it or something in it was a mistake. And they’ll correct it for you if you point it out, but something goes out of the story—it’s not as good. It’s not in their original voice. It’s following your instructions, and somehow, it’s gone.

Greben: In class, if you’re trying to guide a student and the end result is that the story loses its power, would you say a good editor can fix that problem, and walk the line between guidance and—

Salter: Well, I was trying to be a good editor, so I have to say probably not. But a writing student is a little different from a writer who has submitted a manuscript and an editor who’s working on it. The writing student is fresher, less sophisticated—whatever they are, they’re fresh and malleable, and what essence they have belongs to them. I don’t want to make it too poetic, but it’s like the petal of a flower—in a way, you bruise it by messing with it too much. Some of them write really very well.

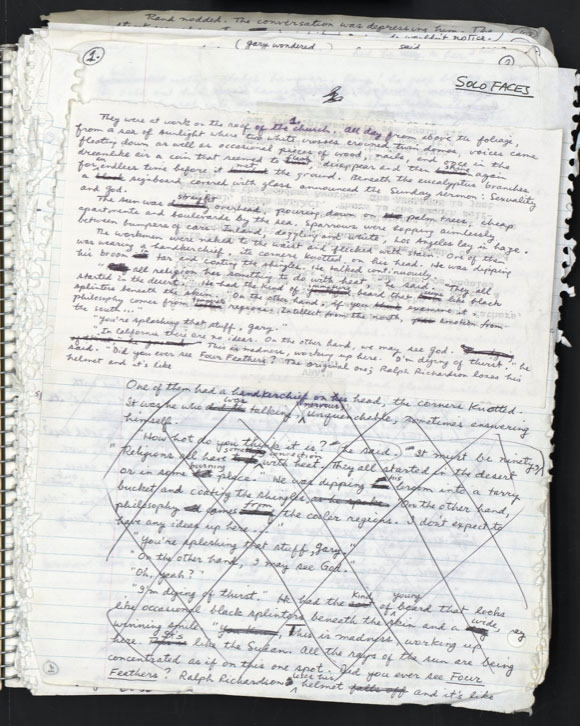

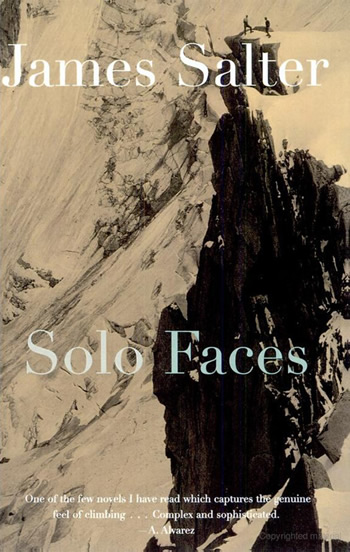

DeWeese: There’s an image early in All That Is of a house or mansion that Bowman believes he saw when he was a child. And there’s this repeated search for a home—we often follow his attempts at a new place to live. It doesn’t seem specific to All That Is, either. A book we haven’t talked about, but Solo Faces—there’s a sense that many of your characters are looking for the place they believe they belong, and not quite finding it. I’m wondering whether that theme of looking for a home is something you think about overtly, or whether your characters seem to become interested in that as you’re writing them.

Salter: That’s what I think. The second of those.

DeWeese: Because that has been an element in more than one book, have you changed your thoughts about what this home is that they’re looking for? Does this place exist?

Salter: Naturally, I think they’re searching for the kind of home that I would like. Usually it’s not specific. In All That Is, it’s quasi-specific. He’s talking about he wants a beautiful room in one episode, in another he’s admiring the house of one of his writers up in the country, it describes that house. When he finally buys a house, it describes that house. So it’s fairly specific about what he would be satisfied with, what he’s looking for. Does that correspond with what I would like? Yeah, I would say so.

DeWeese: Do you have a sense that he finds it? The novel is episodic, and it ends with an episode—

Salter: I don’t think he found the house, but the implication is he found some hope of being happy, being settled. Of course, that’s happened to him before. But I think it ends on a touching note, myself. Here’s a case of—you mentioned, is it written enough? Is this written enough for the reader to see? In that particular instance, maybe not. Maybe I should have written a little more there. But I thought it would be gotten, that it was apparent. No, there’s no indication he’s going to buy a house, or is looking for another house.

DeWeese: You said he’s probably looking for the kind of home that you would like. Do you feel like you found this at some point?

Salter: Well, I never found the perfect house. How are you gonna do that? It’s not easy.

Greben: From a reader’s perspective, I think the end is written plenty. Because again, the reader will take away what he or she wants. If he or she wants to have hope in Bowman’s future, they can have that. If he or she is just, No way…as a reader you can fill in the blanks.

Salter: But is that good? I didn’t intend that, really. I intended to end it more hopefully, a little more decisive, but I didn’t want to go into sentimental—you know, a lot of romance-at-last kind of thing. Anyway, there it is. For me, I understand it.

DeWeese: There’s one other line in the novel—it’s when Beatrice [Bowman’s mother] is getting older and she’s losing track of things, of reality. Again, I marked it because it’s one of the few moments when religion or spirituality is directly addressed. She asks Bowman what he thinks happens after death, and he responds by asking her what she thinks happens. She says, “I think that whatever you believe will happen is what happens.” And the next line reads, “He recognized the truth in it.” It’s a little bit of a magical statement.

Salter: Well, of course that’s an ironic and incomplete answer. It’s just saying that after the last thing you were thinking, there’s no more thinking—so that’s the final thought, and that’s what happens. That’s what I meant by the truth.

DeWeese: I want to thank you for your time—you’ve been more than generous. Are you working on something now?

Salter: I’m not working on anything at the moment. But yes, I’d like to write something more. I think there are plenty of possibilities. I don’t think I’ve used up even my own limited possibilities.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

James Salter’s novels include A Sport and a Pastime, Light Years, and Solo Faces. His story collection, Last Night, was published in 2005. A collection of his non-fiction, There and Then: The Travel Writing of James Salter, also appeared in 2005.

Dan DeWeese is the author of the novels Gielgud and You Don’t Love This Man, and a story collection, Disorder.